Table of Contents

Peripheral Management in RPi

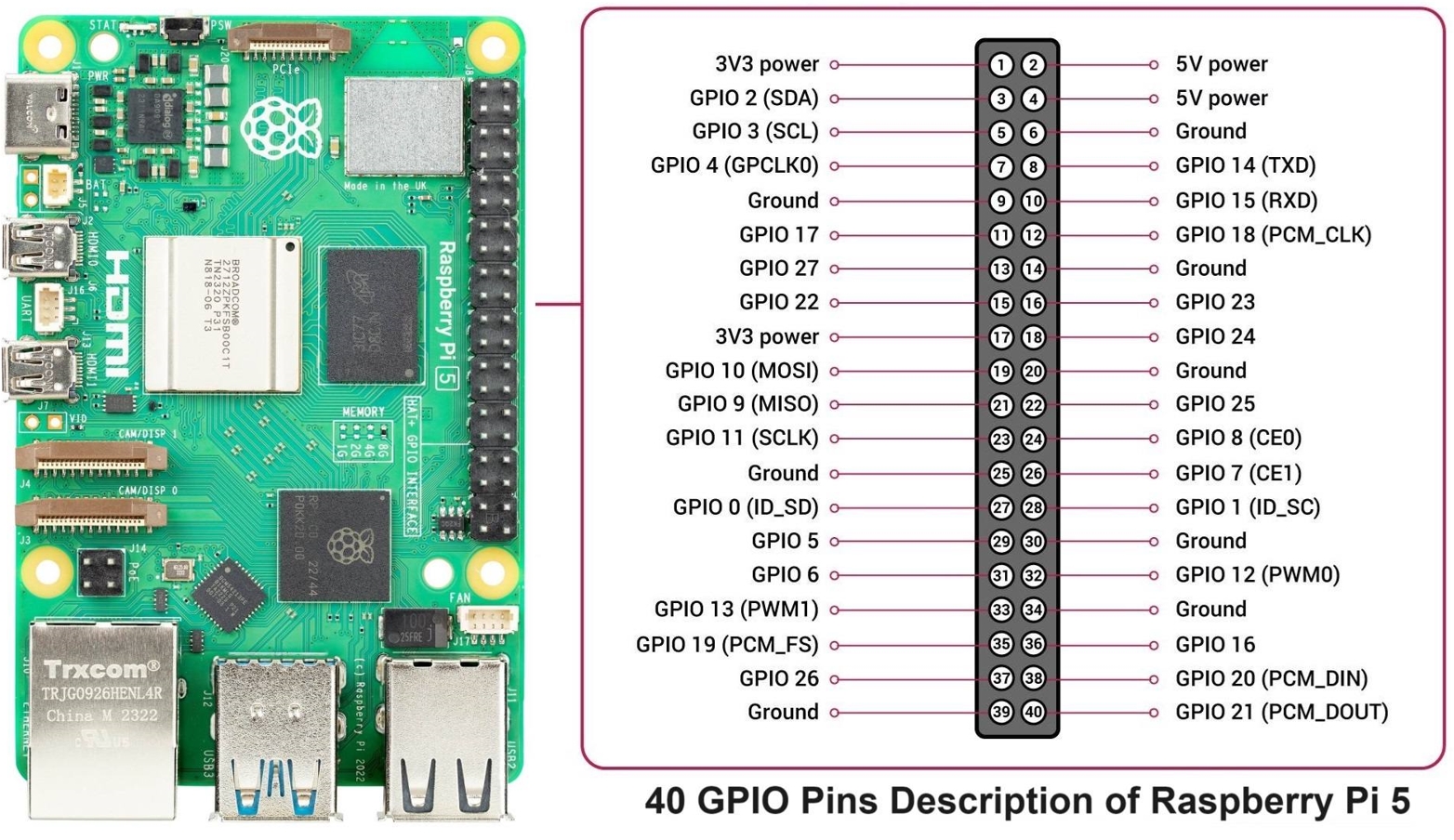

The Raspberry Pi has ported out some General-Purpose Input/Output (GPIO) lines. Several lines share functionality across the board's peripherals. To access peripherals like GPIO, they must be enabled in the Raspberry Pi 5 OS. Many things can be done with the Raspberry Pi's available GPIOs. In the picture below, the GPIOs and their alternative functions (in scope) are shown.

For example, to enable UART communication on GPIO 14 and 15, the “./boot/config.txt” file must be edited by adding these two lines:

dtoverlay=uart0-pi5dtparam=uart0=on

There are libraries designed to work with GPIO and/or communication interfaces such as UART, SPI, and I2C. For example, to work with GPIO, a special library in C or Python can be used, or GPIO can be accessed via memory mapping of IO registers. Note that GPIO parameters must be set before using them as outputs or inputs, like setting pull-up or pull-down resistors, setting direction, etc. On Linux, using libraries such as libgpiod or wiringPi/pigpio can save a lot of time. But these libraries are primarily available in C or even higher-level programming languages. The hardest part is to find proper hardware addresses. The Raspberry Pi5 installer RP1 peripheral controller documentation contains two addresses: System-Address, which is 40-bit long, and Proc-Address, which is 32-bit long. Taking the example of peripherals on the APB0 internal bus, the address in Proc-Address is 0x40000000, but in System-Address it is 0xC040000000. The difference is coloured out. Similar differences appear across all other peripheral buses, and these differences may occur in the code depending on the OS version, installed libraries, and drivers.

General Purpose Inputs and Outputs (GPIO)

Usable GPIO pins on the Raspberry Pi 5 are in IO_BANK0, and this provides information on the addresses available for GPIO programming. Other banks, IO_BANK1 and IO_BANK2, are reserved for internal use inside the board. The base address for IO_BANK0 is 0x400D0000, and the remaining addresses for GPIO programming are documented in the section “3.1.4.Registers” at the RP1 datasheet.

In the previous section, the basic GPIO pin toggling was implemented. GPIOs can be used for many purposes, such as replacing hardware components that are not available on the current board. The technique is called bit-banging. A Raspberry Pi has only one I2C interface, and let's assume that two or more sensors must be connected to the board and share the same I2C device address. This means that only one sensor per I2C channel can be connected, and as the Raspberry Pi has only one interface, only one sensor can be used. With the bit-bang technique, it is possible to create many communication interfaces if at least two GPIO pins are available. Note that the bit-banging technique uses processor power, so there are also limits for the number of interfaces. That’s because I2C must maintain a 100kHz clock rate for successful communication, and bit-banging techniques require significant processor power. Under heavy CPU load, the emulated I2C interfaces may run slower than necessary.

The following code example will be executed in the User space and may require root permissions to access the “/dev/gpiomem” device.

.global _start

.section .text

@ Constants

.equ GPIO_BASE, 0x400D0000

.equ GPFSEL0, 0x00

.equ GPSET0, 0x1C

.equ GPCLR0, 0x28

.equ GPLEV0, 0x34

.equ SDA_BIT, (1 << 2)

.equ SCL_BIT, (1 << 3)

_start:

@ Open /dev/gpiomem (fd=3)

MOV X8, #56 @ syscall openat

MOV X0, #-100 @ AT_FDCWD

LDR X1, =path

MOV X2, #2 @ O_RDWR

MOV X3, #0

SVC #0 @ open -> fd in X0

MOV X19, X0 @ save fd

@ mmap GPIO

MOV X8, #222 @ syscall mmap

MOV X0, #0 @ addr

MOV X1, #4096 @ length

MOV X2, #3 @ PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE

MOV X3, #1 @ MAP_SHARED

MOV X4, X19 @ fd

MOV X5, #0 @ offset

SVC #0

MOV X20, X0 @ base addr

@ configure pins 2,3 as outputs

LDR W1, [X20, #GPFSEL0]

BIC W1, W1, #(0b111 << 6) @ clear bits for GPIO2

ORR W1, W1, #(0b001 << 6) @ set output

BIC W1, W1, #(0b111 << 9) @ clear bits for GPIO3

ORR W1, W1, #(0b001 << 9)

STR W1, [X20, #GPFSEL0]

@ Send start condition: SDA low while SCL high

BL scl_high

BL delay

BL sda_low

BL delay

@ Send byte 0xA5 (1010 0101)

MOV W0, #0xA5

MOV W1, #8

send_bit:

BL scl_low

TST W0, #0x80

BEQ send_zero

BL sda_high

B after_bit

send_zero:

BL sda_low

after_bit:

BL delay

BL scl_high

BL delay

BL scl_low

LSL W0, W0, #1

SUBS W1, W1, #1

B.NE send_bit

@ Stop: SDA high while SCL high

BL sda_low

BL scl_high

BL delay

BL sda_high

@ Exit

MOV X8, #93

MOV X0, #0

SVC #0

@ ---- Subroutines ----

sda_high:

MOV W2, #SDA_BIT

STR W2, [X20, #GPSET0]

RET

sda_low:

MOV W2, #SDA_BIT

STR W2, [X20, #GPCLR0]

RET

scl_high:

MOV W2, #SCL_BIT

STR W2, [X20, #GPSET0]

RET

scl_low:

MOV W2, #SCL_BIT

STR W2, [X20, #GPCLR0]

RET

delay:

MOV W3, #100

delay_loop:

SUBS W3, W3, #1

B.NE delay_loop

RET

.section .rodata

path: .asciz "/dev/gpiomem"

Overall, working with any peripheral requires studying its documentation to identify its base addresses and the offset addresses needed to control it.

Communication interfaces

The hardware can be used to send and receive a byte through I2C. The hardware itself performs all the control over digital signals. Everything that is needed again, find the base addresses for the hardware. Unfortunately, on the Raspberry Pi official homepage, the developers state that all available documentation on peripherals is intended for use with operating systems. On Raspberry Pi 5, the GPIO and the communication interfaces are on a separate chip, the RP1-C0.

In chapter 2 of the RP1-CO documentation, it states that the board has multiple communication interfaces, including 7 I2C interfaces. All the base addresses are listed, but unfortunately, there is no information on how to control the I2C, SPI or UART communication interfaces. Only a few interfaces are available for user use because the Raspberry Pi 5 board has additional hardware that also requires some of those interfaces, or digital lines are used for special purposes. Sometimes, all the digital lines used for communication interfaces are repurposed for other purposes, rendering the communication interfaces useless.

First, it is necessary to determine which interfaces are available on the Raspberry Pi and, of course, to find the device addresses. Another option is to use Linux. To use any communication interface, it must be enabled in the OS. The easiest way is to use the standard Linux i.e. i2c-dev interface, and it can be used with the following function calls:

- open(“/dev/i2c-1”, O_RDWR), close(fd) and exit(0) to access the file descriptor

- write(fd, &tx_byte, 1) to write 1 byte (used to send the byte)

- read(fd, &rx_byte, 1) to read 1 byte (used to receive the byte)

In the assembler code, the I2C device must be opened by calling the OS system function “openat(AT_FDCWD, “/dev/i2c-1”, O_RDWR, 0)”. In the assembler, it will look like :

path_i2c:

.asciz "/dev/i2c-1"

.section .text

.global _start

_start:

MOV X0, #-100 @ #AT_FDCWD

LDR X1, =path_i2c

MOV X2, #2 @ O_RDWR - read and write

MOV X3, #0

MOV X8, #56 @ #SYS_openat

SVC #0

After the system call is executed, the X0 register will hold the file descriptor that can be used for future system calls. It should be stored and in the example register X19 is used:” MOV X19, X0”. Later on, to send or read one byte, system calls WRITE or READ are used, like in the code below:

I2Cbyte:

.byte 0xAB

MOV X0, X19

LDR X1, =I2Cbyte

MOV X2, #1 @ nuber of bytes

MOV X8, #64 @#64=SYS_write #63=SYS_read

SVC #0

The code sends the data; the device address is not set in these examples. The system call with number #64 generates the START signal, sends the device address (with the write bit set), sends the .byte value, and finally sends the STOP signal. After the system call is executed, the X0 register holds the number of bytes transmitted. After this example code executes, the value must be equal to 1.

To unlock the full potential of any communication interface on Raspberry Pi, it will take a lot of effort to find the register addresses, digital lines, and their parameters, and even then, something will be missing. For example, the same code that works on Raspberry Pi version 3 or 4 will not work on version 5. The hardware addresses differ, and it seems the Operating System is translating them into 32-bit addresses. The communication interface depends heavily on the Operating System kernel version, kernel modules, and configuration. It is recommended to use system calls for other communication interfaces as well, as experimenting with the hardware without complete documentation is not recommended. As a result, the code may take harmful actions, damaging the Raspberry Pi.

Pulse Width Modulation

Basically, with a single GPIO line, you can do a lot: control almost any hardware, read or take measurements, generate wireless signals, and more. Of course, it is easier to control hardware designed for specific purposes, such as I2C communication in the previously described examples. As with the bit-banging technique, it is possible to generate periodic digital signals and control their duty cycle.

In Raspberry Pi 5, the RP1 chip documentation contains much more information on pulse-width modulation than on basic communication interfaces. PWM registers are on the internal peripheral bus; the base addresses for PWM0 and PWM1 are 0x40098000 and 0x4009C000, respectively. This hardware is located in the RP1 chip and accessed through PCIe. The Linux OS sets up hardware address mapping, and this mapping is not exposed as a simple fixed physical address that can be accessed with just LDR/STR instructions from user space. To access the PWM registers, it is necessary to execute the code at least at the EL1 level and to know already the PCIe mapping, or the mapping can be implemented manually. Again, this is too advanced and carries a risk of breaking something.

Before proceeding, the base addresses must be checked at least three times (NO JOKES) and, if needed, replaced. The PWM0_BASE and IO_BANK0_BASE addresses are already mapped and known for the Raspberry Pi 5. In the example, the GPIO line 18 will be used.

.equ PWM0_BASE, 0xXXXXXXXX @ filled in by platform code .equ IO_BANK0_BASE, 0xYYYYYYYY @ filled in by platform code .equ PWM_CHAN2_CTRL, 0x34 .equ PWM_CHAN2_RANGE,0x38 .equ PWM_CHAN2_DUTY, 0x40 .equ GPIO18_CTRL, 0x094 .equ FUNC_PWM0_2, 0xZZ @ FUNCSEL value for PWM0[2] on GPIO18

These are the constants used later on in the code. Note that three constants are holding dummy values – these values depend on the hardware. The rest of the code will control GPIO18 and generate a pulse at the specified frequency and duty cycle. The frequency and duty cycle parameters can be passed to the code. The X0 register will hold the period value, and the X1 register will hold the duty cycle value.

.global pwm_init_chan2

pwm_init_chan2:

LDR X2, =IO_BANK0_BASE

ADD X2, X2, #GPIO18_CTRL

LDR W3, [X2] @ read current CTRL

BIC W3, W3, #0x1f @ clear FUNCSEL bits [4:0]

ORR W3, W3, #FUNC_PWM0_2 @ set FUNCSEL to FUNC_PWM0_2

STR W3, [X2]

At this moment, the GPIO line is ready and internally connected to the PWM generator. The following code lines provide the PWM generator with all the necessary parameters: period and duty cycle.

LDR X4, =PWM0_BASE

ADD X5, X4, #PWM_CHAN2_RANGE @ X5=PWM0_BASE+PWM_CHAN2_RANGE

STR W0, [X5] @ low 32 bits used

ADD X5, X4, #PWM_CHAN2_DUTY

STR W1, [X5]

Note that the code uses only 32-bit values of the X0 and X1 registers, where the input arguments are stored. The last step is to activate the PWM generator for Channel 2, setting its parameters, such as the PWM generation mode to trailing edge.

ADD X5, X4, #PWM_CHAN2_CTRL @ x5=PWM0_BASE+PWM_CHAN2_CTRL

LDR W6, [X5]

@ Check the datasheet -> clear existing MODE bits (example)

BIC W6, W6, #(0x7)

@ set mode to trailing-edge

ORR W6, W6, #0x1

@ set enable bit (placeholder) check datasheet

ORR W6, W6, #(1 << 8)

STR W6, [X5]

RET

This code can be used as a kernel module, but it cannot be executed directly from a regular user program on Pi OS. That’s because the mapping is involved, and with that, the kernel is also involved (because of the PCIe mapping).

The second approach

The second approach is similar to I2C communication: it uses system calls. The Raspberry Pi must be prepared with a device-tree overlay, for example, “dtoverlay=pwm-2chan,pin=18,func=4”. Note that to enable PWM, the string must be used, not just the value. Now it is time to create system calls. In the I2C example, three different system calls were made; the only difference between the code fragments is the system call value and arguments. Everything needed to activate PWM generation is to open the file, write some variables to it, and save it by closing it.

@ void write_file(const char *path, const char *str)

write_file:

@ x0 = path, x1 = string

@ openat(AT_FDCWD, path, O_WRONLY, 0)

MOV X2, #O_WRONLY

MOV X3, #0

MOV X8, #SYS_OPENAT

MOV X4, #AT_FDCWD

MOV X0, X4 @ AT_FDCWD

@ x1 already holds path

SVC #0 @ X0 = fd

MOV X19, X0 @ save fd

@ find string length

MOV X0, X1 @ pointer to string

1: LDRB W2, [X0], #1

CBZ W2, 2f @ jump to label 2 (f means forward)

B 1b @ jump to label 1 (b means backward)

2:

@ now X0 points past NUL; length = (X0 - 1) - str

SUB X2, X0, X1 @ remove the NUL as it is not needed

SUB X2, X2, #1

@ write(fd, str, len)

MOV X0, X19

MOV X8, #SYS_write

SVC #0

@ close(fd)

MOV X0, X19

MOV X8, #SYS_close

SVC #0

RET

Now, the code to activate the PWM generator sets the period and duty. It is necessary to know which file to edit and which values to write to the files. Required constants for this example are:

.equ SYS_openat, 56

.equ SYS_write, 64

.equ SYS_close, 57

.equ SYS_exit, 93

.equ AT_FDCWD, -100

.equ O_WRONLY, 1

.section .rodata

path_export:

.asciz "/sys/class/pwm/pwmchip0/export"

path_period:

.asciz "/sys/class/pwm/pwmchip0/pwm0/period"

path_duty:

.asciz "/sys/class/pwm/pwmchip0/pwm0/duty_cycle"

path_enable:

.asciz "/sys/class/pwm/pwmchip0/pwm0/enable"

str_chan0:

.asciz "0\n"

str_period:

.asciz "20000000\n" @ 20 ms period = 20000000 ns (for example, servo-style period)

str_duty:

.asciz "5000000\n" @ 5 ms high time = 5000000 ns (25% duty)

str_enable:

.asciz "1\n" @ enable PWM

And the main code, which sets all values:

LDR X0, =path_export @ export PWM channel 0

LDR X1, =str_chan0

BL write_file

LDR X0, =path_period @ set period

LDR X1, =str_period

BL write_file

LDR X0, =path_duty @ set duty_cycle

LDR X1, =str_duty

BL write_file

LDR X0, =path_enable @ enable PWM generation

LDR X1, =str_enable

BL write_file

MOV X0, #0 @ exit

MOV X8, #SYS_exit

SVC #0

The code can be upgraded to accept the arguments: period and duty cycle. This would be similar to the write_file function, which takes two arguments.