Table of Contents

Basic Instructions and Operations

Most of the program code consists of basic instructions that perform arithmetic operations, move data, perform logical operations, and control I/O digital lines, among other tasks. This section provides an introduction to the basic instructions of the ARM v8 instruction set.

Arithmetical instructions

All arithmetical operations are performed directly on the processor's registers. The most common instructions are the same ones we use every day to add two or more values together, subtract one value from another, multiply two values, or divide one value by another. In ARM assembly, the ADD, SUB, MUL, and DIV instructions perform the same function. All these instructions and other arithmetic instructions require that both values be placed in the registers. At this moment, we assume that all values in the registers are preloaded and ready to use, as demonstrated in the following instruction examples.

ADD X0, X1, X2 @ adds the X1 and X2 values X0= X1 + X2

If the postfix S is added (ADDS), the status register is updated.

ADDS X0, X1, X2 @ X0 = X1 + X2 Status register SR is updated

ADCS X0, X1, X2 @ X0 = X1 + X2 + C from the SR register. The status register SR is updated

A status update is helpful for the upcoming conditional instructions. ADC or ADCS are standard in multi-word arithmetic (e.g., 128-bit math).

The SUB and DIV instructions rely on the order of the used variables to preserve a correct mathematical expression.

SUB X0, X0, #1 @ X0 = X0 – 1

SUB X0, X1, #1 @ X0 = X1 – 1

UDIV X3, X4, X5 @ X3 = X4 / X5

All these arithmetical instructions have additional options, such as an optional shift of the second source operand. The DIV instruction must have a prefix of S for Signed (SDIV) or U for Unsigned (UDIV) divide operations. Prefix S preserves the sign of the result, depending on the signs used for the operands. The prefix U always returns a positive value.

Some instructions can be combined to achieve better computational performance. In such cases, the first arithmetic operation is performed on the second source register, and then the instruction's operation is performed. Such instructions are: MADD, MSUB, SMADDL, SMSUBL, UMADDL and UMSUBL. Basically, all the listed instructions are MADD and MSUB, but with different options. Let's look at MADD and MSUB instructions.

MADD X1, X2, X3, X4 @ X1 = X4 + X2*X3

MSUB X1, X2, X3, X4 @ X1 = X4 - X2*X3

Before performing addition or subtraction, first multiply the registers X2 and X3 (the second and third operands given to the instruction), and then perform the addition or subtraction. The prefixes S and U define whether the result can be a signed value or only a positive value (unsigned value). The postfix L, like SMSUBL or UMADDL, specifies that only 32-bit register values are used when multiplying the second and third operands. The remaining operands are 64-bit register values.

The next ARM version, ARMv8.3, processors are built by default with a PAC (Pointer Authentication) system. Earlier architectures must have been checked to see whether the PAC system is available. This enables the system to protect against pointer errors or corruption and adds additional arithmetic instructions. The system's security level can be significantly increased by marking and checking pointers. PAC adds a signature to the pointer, allowing verification that it has not been tampered with before use. As a result, additional postfixes for the ADD instruction, such as ADDG and ADDPT, are added. While these operations are less common in simple programs, they are powerful tools when writing optimised and secure code.

The ADDG instruction means ADD with Tag and is focused on pointers. The Tag is used to mark the pointer with a small identifier, allowing detection of pointer corruption or incorrect usage, among other options. Primarily, these instructions are used to authenticate pointers and ensure memory safety, for example, by tracking the boundaries of memory regions.

For example: ADDG X0, X1, #16, #5

CPU takes the pointer from the X1 register and adds the first constant #16 multiplied by 16. The pointer X0 points to X1+256 and has a tag set to #5 or in binary form 01012. X0 now points 256 bytes ahead of the memory address stored in the register X1.

Postfix PT adds support for pointer tagging or authentication. For example, ADDPT adds authenticated pointers and preserves the PAC.

ADDPT X0, X1, X2

The X1 register contains an authenticated pointer; this can be signed before with the PACIA or other PAC-enabled instruction. Register X2 is the value, an offset from the X1 pointer. The result is a pointer with an offset and tagged with the same tag as the X1 pointer. Such arithmetic operations are also available for the SUB instruction, but not available for the MUL multiplication and DIV division instructions. Such a system enables powerful system-level encryption.

Instruction options

All assembly language types use similar mnemonics for arithmetic operations (some may require additional suffixes to identify some options for the instruction). A32 assembly instructions have specific suffixes to make commands executed conditionally, and those four most significant bits for many instructions give this ability. Unfortunately, there is no such option for A64, but there are special conditional instructions that we will describe later.

We looked at a straightforward instruction and its exact machine code in the previous section. Examining machine code for each instruction is a perfect way to learn all the available options and restrictions. To help understand and read the instruction set documentation, another example of the ADD instruction in the A64 instruction set will be provided.

The ADD instruction: let's first look at the assembler instruction that adds two registers and stores the result in a third register.

ADD X0, X1, X2 @X0 = X1 + X2

We need to look at the instruction set documentation to determine the possible options for this instruction. The documentation lists three main differences between the ADD instructions. Despite that, for the data manipulation instruction, the ‘S’ suffix can be added to update the status flags in the processor Status Register.

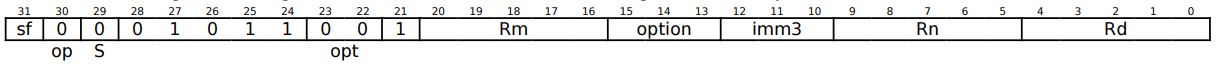

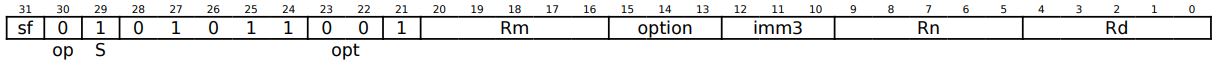

1.The ADD and ADDS instructions with extended registers:

ADD X3, X4, W5, UXTW @X3 = X4 + W5

ADDS X3, X4, W5, UXTW @X3 = X4 + W5 and update the status flags

The machine code representation of the assembler instruction would be like:

ADDS X3, X4, W5, UXTW

- Rd = X3 @ pointer to the register where the result will be stored

- Rn = X4 @ pointer to the First operand of the provided operands

- Rm = W5 @ pointer to the Second operand of the provided operands, which will be extended to 64 bits

We already know that the ‘sf’ bit identifies the length of the data (32 or 64 bits). The main difference between these two instructions is in the ‘S’ bit. The same is in the name of the instruction. The ‘S’ bit is meant to signal to the processor that the status bits should be updated after instruction execution. These status bits are crucial for conditions. The 30th ‘op’ bit and ‘opt’ bits are fixed and not used for this instruction. The three option bits (13th to 15th) extend the operation. These bits are used to extend the second source (Rm) operand. This is handy when the source operands differ in length, such as when the first operand is 16-bit wide and the second is 8-bit wide. The second register must be extended to maintain the data alignment. Overall, there are three bits: 8 different options to extend the second source operand. The table below explains all these options. Let's look only at those options; the bit values are irrelevant for learning the assembler.

| UXTB or SXTB | Unsigned or Signed byte (8-bit) is extended to a word (32-bit) |

| UXTH or SXTH | Unsigned or Signed halfword (16-bit) is extended to word (32-bit) |

| UXTW or SXTW | Unsigned/Signed word (32-bit) is extended to double word (64-bit) |

| UXTX, SXTX or LSL | Unsigned/Signed double word (64-bit) is extended to double word (64-bit), and there is no use for such extension with the unsigned data type. |

For the UXTX, the LSL shift is preferred if the ‘imm3’ bits are set from 0 to 4. Other ranges are reserved and unavailable because the result can be unpredictable. Moreover, this shift is only available if the ‘Rd’ or the ‘Rn’ operands are equal to ‘11111’, which is the stack pointer (SP). In all other cases, the UXTX extension will be used. In the conclusion for this instruction type, it is handy when the operands are of different lengths, but that’s not all. The shift provided to the second operand allows us to multiply it by 2, 4, 8 or 16, but it works only if the destination register is 64 bits wide (the Xn registers are used). The shift amount is restricted to 4 bits only, even when the ‘imm3’ can identify the larger values. Also, the SXTB/H/W/X are used when the second operand can store negative integers.

ADDS X3, X4, W5, SXTX #2

/ *extend the W5 register to 64 bits and then shift it by 2 (LSL), which makes a multiplication by 4 (W5=W5*4). Add the multiplied value to the X4+(W5*4), store the result in the X3 register X3 = X4 + (W5*4) */

ADD X3, X4, W5, UXTX #1

/ *Take the lowest byte from W5 (W5[7:0])

Zero-extend it to 64-bit

Shifts left by 1 (multiply by 2)

Add to X4 and store in X3*/

ADD X7, X8, W9, SXTX #2

/ * Take W9[15:0], sign-extend to 64 bits without shifting; Add to X8 and store in X7; X7 = X8 + W9[15:0] */

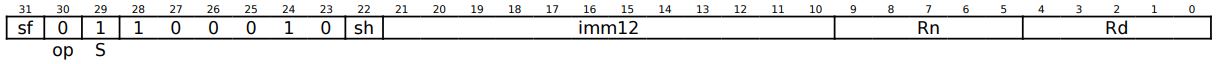

2.The ADDS (ADD) instructions with immediate value: In machine code, it is possible to determine the maximum value that can be added to a register. The ‘imm12’ bits limit the value to 0-4095. Besides that, the ‘sh’ bit allows to shift left (LSL) the immediate value by 12 bits.

Examples with immediate the ADD instruction

ADDW0,W1,#100@W0 = W1 + 100 - Basic 32-bit ADD.@ Add 100 to W1, store the result in W0 and no shift is performed

ADDX0,X1,#4095Basic 64-bit ADD.@ Add 4095 to X1, stores in X0

ADDX2,X3,#1,LSL,#12@ 64-bit ADD with shifted immediate (LSL #12)@ Add 4096 to X3 (1 « 12 = 4096)@ Store the result in X2

ADDW5,W6,#2,LSL,#12@ 32-bit ADD with shifted immediateAdd 8192 to W6 and store the result in W5 (2 « 12 = 8192)

ADDX4,SP,#256,@ Using SP as base register@ Add 256 to SP. Useful for frame setup or stack management

ADDSX7,X8,#42,@ ADDS (immediate) – flag-setting@ Add 42 to X8, store the result in X7 and finally update condition flags (NZCV)

ADDSX9,X10,#3,LSL,#12@ ADDS with shifted immediate@ Add 12288(3 « 12 = 12288) to X10, store the result in X9@ Update condition flags stored in status register

ADDSX11,SP,#512,@ ADDS with SP base@ Add 512 to SP, store the result in X11 and update condition flags

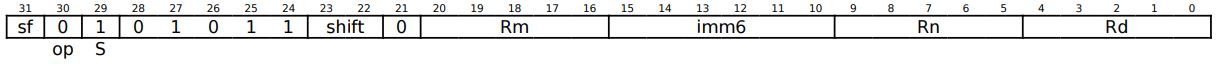

3.The ADDS (ADD) instruction with a shifted register: The final add instruction type adds two registers together, with one register shifted; the shift can be LSL (Logical Shift Left), LSR (Logical Shift Right), or ASR (Arithmetic Shift Right). The fourth shift option is not available. The number of bits in the ‘imm6’ field identifies the number of bits to be shifted for the ‘Rm’ register before it is added to the ‘Rn’ register.

Similar options are available for many other ARMv8 instructions. The instruction set documentation may provide the necessary information to determine the possibilities and restrictions on instruction usage. By examining the instruction's binary form, it is possible to identify its capabilities and limitations. Assembler code is converted to binary, and the final binary code for the instruction depends on the provided operands and, if available, options.

Data copy/move instructions

Remember, the processor primarily performs operations on data stored in registers. The data must be loaded into registers, and the result must be stored back in memory. For example, to change the value stored at a particular memory address, the ARM would require three instructions. First, the value from memory needs to be loaded into a register, then modified, and finally stored back into the memory from the register. Other architectures, such as x86, may allow operations on data directly in memory without register use.

The LDR and STR are basic instructions that load data from memory into a register and store data from a register into memory, respectively.

LDR X0, [X1] @ fill the register X0 with the data located at address stored in X1 register

STR X1, [X2] @ store the content from register X1 into the memory at memory address given in the X2 register

The LDR instruction loads the data from the memory address pointed to in the X1 register into the destination register X0. The register in square brackets, [X1], is called the base register because its value is used as a memory address. Similarly, the STR instruction stores data from the X1 register to the memory location specified by the X2 register.

If the register holding the memory address must be updated after each memory access, then post-indexed or pre-indexed modes can be used. Pre-indexed mode updates the base register before reading the value from memory. Post-indexed mode will update the base register after reading the value from memory.

LDR X0, [X1, #8]! @ Read the data located at address X1+8 and write into register X0 {PRE-INDEXED MODE X1 = X1 + 8}

LDR X6, [X7], #16 @ loads a value to X6 register and then increases X7 by 16. {POST-INDEXED MODE X7 = X7 + 16}

STR X6, [X7], #16 @ Store the value and then increase X7 by 16.

There is also a third option: using the offset value. This option must be used with caution because the offset value is multiplied by 8 (8 bytes).

LDR X0, [X1, #8] @ Read the data located at address X1+8*8 and write into register X0 {X1 = X1 + 8*8}

Load and store instructions have the most additional options, more than for the arithmetical and logical operations. For example, the LDADD instruction combines a load and an arithmetic operation. This is a part of the so-called atomic operations. The LDADD instruction atomically loads a value from memory, adds the value held in a register, and finally stores the result back in memory at a different location. NOTE that the registers used in this instruction must not be the same. This is something like what would be for the x86 architecture. Unfortunately, no other arithmetic operations are available besides addition.

LDADD W1, W2, [X0]

The register X0 holds a memory address. The data/value is loaded into the W2 register, and then the value is added to the W1 register value, after which the new value [X0]+W1 is stored back into memory at the exact location pointed by [X0]. Basically, the W2 register now holds the [X0]- pointed data that was present before the W1 value was added. Similar instructions are available to perform atomic logic operations on the memory data.

To copy content from one register to another, the MOV instruction is used. The FMOV instruction can also copy floating-point values. These instructions allow typecasting a floating-point value to an integer and vice versa. Here are some independent instruction examples

MOV X1, X0 @ X1 = X0 (64 bit register copy)

MOV W1, W0 @ W1 = W0 (32 bit register copy)

FMOV S1, S0 @ float → float (32-bit floating-point copy between vector registers)

FMOV X0, D1 @ FP64 → int64 (copy from vector register to general-purpose register)

FMOV D2, X3 @ int64 → FP64 (copy from general-purpose register to vector register)

MOV V1.16b, V0.16b @ vector register copy one byte

The MOV instructions can also be used to write a value into the register immediately. In the following example, all instructions are executed one by one:

MOV X0, #123 @ assign value 291 to the register

MOVZ X0, #0x1234, LSL #48 @ X0 = 0x1234 0000 0000 0000. The X0 value gets overvritten

MOVK X0, #0xABCD, LSL #0 @ X0 = 0x1234 0000 0000 ABCD, if before instruction execution the register value was 0x1234 0000 0000 0000

Data copy/move instructions

These instructions do not work with values that require arithmetic operations. Still, they are mainly used to manipulate individual bits in registers, widely used to test or verify values, and to perform other functions. Basic logic instructions for AARCH64 are:

AND X0, X1, X2 @ logical AND between X1 and X2, result is stored in X0

ORR X6, X7, X8 @ logical OR between X7 and X8, result is stored in X6

EOR X12, X13, X14 @ logical XOR between X13 and X14, result is stored in X12

NEG X24, X25 @ logical NOT, X24 is set to inverted X25

Remember that most instructions, which operate with registers, can update the status register by adding the postfix S at the end of the instruction. Logical instructions are fundamental for low-level programming. These instructions allow taking control over bits and are widely used in system code, device drivers, and embedded systems. Some instructions can perform combined bitwise operations, like ORN, which performs an OR operation with the inverted second operand.