This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Energy Efficient Coding

Assembler code is assembled into a single object code. Compilers, instead, take high-level language code and convert it to machine code. And during compilation, the code may be optimised in several ways. For example, there are many ways to implement statements, FOR loops or Do-While loops in the assembler. There are some good hints for optimising the assembler code as well, but these are just hints for the programmer.

- Take into account the instruction execution time (or cycle). Some instructions take more than one CPU cycle to execute, and there may be other instructions that achieve the desired result.

- Try to use the register as much as possible without storing the temporary data in the memory.

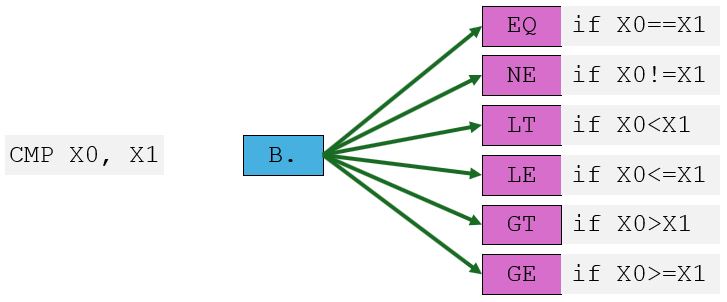

- Eliminate unnecessary compare instructions by doing the appropriate conditional jump instruction based on the flags that are already set from a previous arithmetic instruction. Remember that arithmetic instructions can update the status flags if the postfix

Sis used in the instruction mnemonic. - It is essential to align both your code and data to get a good speedup. For ARMv8, the data must be aligned on 16-byte boundaries. In general, if alignment is not used on a 16-byte boundary, the CPU will eventually raise an exception.

- And yet, there are still multiple hints that can help speed up the computation. In small code examples, the speedup will not be noticeable. The processors can execute millions of instructions per second.

Processors today can execute many instructions in parallel using pipelining and multiple functional units. These techniques allow the reordering of instructions internally to avoid pipeline stalls (Out-of-Order execution), branch prediction to guess the branching path, and others. Without speculation, each branch in the code would stall the pipeline until the outcome is known. These situations are among the factors that reduce the processor's computational power.

Speculative instruction execution

Let's start with an explanation of how speculation works. The pipeline breaks down the whole instruction into small microoperations. The first microoperation (first step) is to fetch the instruction from memory. The second step is to decode the instruction; this is the primary step, during which the hardware is prepared for instruction execution. And of course, the next step is instruction execution, and the last one is to resolve and commit the result. The result of the instruction is temporarily stored in the pipeline buffer and waits to be stored either in the processor’s registers or in memory.

CMP X0, #0

B.EQ JumpIfZeroLabel

ADD X1, X1, #1 @ This executes speculatively while B.EQ remains unresolved

The possible outcomes are shown in the picture below.

In the example above, the comparison is made on the X0 register. The next instruction creates a branch to the label. In the pipeline, while B.EQ instruction is being executed; the next instruction is already prepared to be executed, if not already (by speculation). When the branch outcome becomes known, the pipeline either commits the results (if the prediction was correct) or flushes the pipeline and re-fetches from the correct address (if the prediction was wrong). In such a way, if the register is not equal to zero, processor speculation wins in performance; otherwise, the third instruction result is discarded, and any microoperation for this instruction is cancelled—the processor branches to a new location.

From the architectural point of view, the speculations with instructions are invisible, as if those instructions never ran. But from a microarchitectural perspective (cache contents, predictors, buffers), all speculation leaves traces. Regarding registers, speculative updates remain in internal buffers until commit. No architectural changes happen until then. Regarding memory, speculative stores are not visible to other cores or devices and remain buffered until committed. But the speculative loads can occur. They may bring the data into cache memory even if it’s later discarded.

In this example, the AMR processor will perform speculative memory access:

LDR X0, [X1]

STR X2, [X3]

If the registers X1 and X3 are equal, the store may affect the load result. Processor instead of stalling until it knows for sure it will speculatively issue the load. The processor performs loads earlier to hide memory latency and keep execution units busy. The X1 register result may not be known for sure, since previous instructions may have computed it. If aliasing is later detected, the load result is discarded and reissued, a process called speculative load execution. It’s one of the primary sources of side-channel leaks (Spectre-class vulnerabilities) because speculative loads can cache data from locations the program shouldn’t have access to.

Barriers(instruction synchronization / data memory / data synchronization / one way BARRIER)

Many processors today can execute instructions out of the programmer-defined order. This is done to improve performance, as instructions can be fetched, decoded, and executed in a single cycle (instruction stage). Meanwhile, memory access can also be delayed or reordered to maximise throughput on data buses. Mostly, this is invisible to the programmers.

The barrier instructions enforce instruction order between operations. This does not matter whether the processor has a single core or multiple cores; these barrier instructions ensure that the data is stored before the next operation with them, that the previous instruction result is stored before the next instruction is executed, and that the second core (if available) accesses the newest data. ARM has implemented special barrier instructions to do that: ISB, DMB, and DSB. The instruction synchronisation barrier (ISB) ensures that subsequent instructions are fetched and executed after the previous instruction's results are stored (the previous instruction's operations have finished). A data memory barrier (DMB) ensures that the order of data read or written to memory is fixed. And the Data synchronisation barrier (DSB) ensures that both the previous instruction and the data access are complete and that the order of data access is fixed.

Since the instructions are prefetched and decoded ahead of time, those earlier fetched and executed instructions might not yet reflect the newest state. The ISB instruction – it forces the processor to stop fetching the next instruction before the previous instruction operations are finished. This type of instruction is required to ensure proper changes to a processor's control registers, memory access permissions, exception levels, and other settings. These instructions are not necessary to ensure the equation is executed correctly, unless the equation is complex and requires storing temporary variables in memory.

MRS X0, SCTLR_EL1 @ Read system control register

ORR X0, X0, #(1 « 0) @ Set bit 0 (enable MMU)

MSR SCTLR_EL1, X0 @ Write back

ISB @ Ensure new control state takes effect

The code example ensures that the control register settings are stored before the following instructions are fetched. The setting enables the Memory Management Unit and updates new address translation rules. The following instructions, if prefetched without a barrier, could operate under old address translation rules and result in a fault. Sometimes the instructions may sequentially require access to memory, and situations where previous instructions store data in memory and the next instruction is intended to use the most recently stored data. Of course, this example is to explain the data synchronisation barrier. Such an example is unlikely to occur in real life. Let's imagine a situation where the instruction computes a result and must store it in memory. The following instruction must use the result stored in memory by the previous instruction.

The first problem may occur when the processor uses special buffers to maximise data throughput to memory. This buffer collects multiple data chunks and, in a single cycle, writes them to memory. The buffer is not visible to the following instructions so that they may use the old data rather than the newest. The data synchronisation barrier instruction will solve this problem and ensure that the data are stored in memory rather than left hanging in the buffer.

Core 0:

STR W1, [X0] @ Store the data

DMB ISH @ Make sure that the data is visible

STR W2, [X3] @ store the function status flag

Core 1:

LDR W2, [X3] @ Check the flags

DMB ISH @ Ensure data is seen after the flag

LDR W1, [X0] @ Read the data (safely)

In the example, the data memory barrier will ensure that the data is stored before the function status flag. The DMB and DSB barriers are used to ensure that data are available in the cache memory. And the purpose of the shared domain is to specify the scope of cache consistency for all inner processor units that can access memory. These instructions and parameters are primarily used for cache maintenance and memory barrier operations. The argument that determines which memory accesses are ordered by the memory barrier and the Shareability domain over which the instruction must operate. This scope effectively defines which Observers the ordering imposed by the barriers extends to.

In this example, the barrier takes the parameter; the domain “ISH” (inner sharable) is used with barriers meant for inner sharable cores. That means the processors (in this area) can access these shared caches, but the hardware units in other areas of the system (such as DMA devices, GPUs, etc.) cannot. The “DMB ISH” forces memory operations to be completed across both cores: Core0 and Core1. The ‘NSH’ domain (non-sharable) is used only for the local core on which the code is being executed. Other cores cannot access that cache area and are also not affected by the specified barrier. The ‘OSH’ domain (outer sharable) is used for hardware units with memory access capabilities (like GPU). All those hardware units will be affected by this barrier domain. And the ‘SY’ domain forces the barrier to be observed by the whole system: all cores, all peripherals – everything on the chip will be affected by barrier instruction.

These domain have their own options. These options are available in the table below.

| Option | Order access (before-after) | Shareability domain |

|---|---|---|

| OSH | Any-Any | Outer shareable |

| OSHLD | Load-Load, Load-Store | Outer shareable |

| OSHST | Store-Store | Outer shareable |

| NSH | Any-Any | Non-shareable |

| NSHLD | Load-Load, Load-Store | Non-shareable |

| NSHST | Store-Store | Non-shareable |

| ISH | Any-Any | Inner shareable |

| ISHLD | Load-Load, Load-Store | Inner shareable |

| ISHST | Store-Store | Inner shareable |

| SY | Any-Any | Full system |

| ST | Store-Store | Full system |

| LD | Load-Load, Load-Store | Full system |

Order access specifies which classes of accesses the barrier operates on. A “load-load” and “load-store” barrier requires all loads to be completed before the barrier occurs, but it does not require that the data be stored. All other loads and stores must wait for the barrier to be completed. The store-store barrier domain affects only data storing in the cache, while loads can still be issued in any order around the barrier. Meanwhile, “any-any” barrier domain requires both loading and storing the data to be completed before the barrier. The next ongoing load or store instructions must wait for the barrier to complete.

All these barriers are practical with high-level programming languages, where unsafe optimisation and specific memory ordering may occur. In most scenarios, there is no need to pay special attention to memory barriers in single-processor systems. Although the CPU supports out-of-order and predictive execution, in general, it ensures that the final execution result meets the programmer's requirements. In multi-core concurrent programming, programmers need to consider whether to use memory barrier instructions. The following are scenarios where programmers should consider using memory barrier instructions.

- Share data between multiple CPU cores. Under the weak consistency memory model, a CPU's disordered memory access order may cause contention for access.

- Perform operations related to peripherals, such as DMA operations. The process of starting DMA operations is usually as follows: first, write data to the DMA buffer; second, set the DMA-related registers to start DMA. If there is no memory barrier instruction in the middle, the second-step operations may be executed before the first step, causing DMA to transmit the wrong data.

- Modifying the memory management strategy, such as context switching, requesting page faults, and modifying page tables.

In short, the purpose of using memory barrier instructions is to ensure the CPU executes the program's logic rather than having its execution order disrupted by out-of-order and speculative execution.