This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Energy Efficient Coding

Assembler code is assembled into a single object code. Compilers, instead, take high-level language code and convert it to machine code. And during compilation, the code may be optimised in several ways. For example, there are many ways to implement statements, FOR loops or Do-While loops in the assembler. There are some good hints for optimising the assembler code as well, but these are just hints for the programmer.

- Take into account the instruction execution time (or cycle). Some instructions take more than one CPU cycle to execute, and there may be other instructions that achieve the desired result.

- Try to use the register as much as possible without storing the temporary data in the memory.

- Eliminate unnecessary compare instructions by doing the appropriate conditional jump instruction based on the flags that are already set from a previous arithmetic instruction. Remember that arithmetic instructions can update the status flags if the postfix

Sis used in the instruction mnemonic. - It is essential to align both your code and data to get a good speedup. For ARMv8, the data must be aligned on 16-byte boundaries. In general, if alignment is not used on a 16-byte boundary, the CPU will eventually raise an exception.

- And yet, there are still multiple hints that can help speed up the computation. In small code examples, the speedup will not be noticeable. The processors can execute millions of instructions per second.

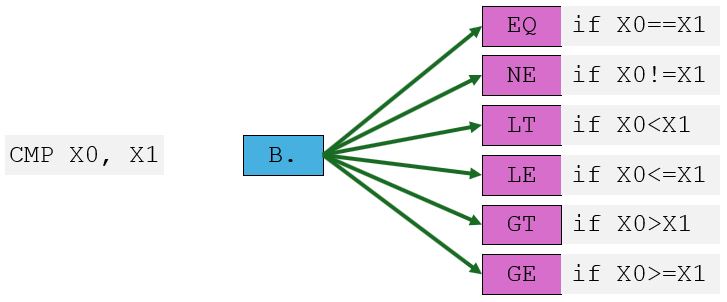

Processors today can execute many instructions in parallel using pipelining and multiple functional units. These techniques allow the reordering of instructions internally to avoid pipeline stalls (Out-of-Order execution), branch prediction to guess the branching path, and others. Without speculation, each branch in the code would stall the pipeline until the outcome is known. These situations are among the factors that reduce the processor's computational power.

Speculative instruction execution

Let's start with an explanation of how speculation works. The pipeline breaks down the whole instruction into small microoperations. The first microoperation (first step) is to fetch the instruction from memory. The second step is to decode the instruction; this is the primary step, during which the hardware is prepared for instruction execution. And of course, the next step is instruction execution, and the last one is to resolve and commit the result. The result of the instruction is temporarily stored in the pipeline buffer and waits to be stored either in the processor’s registers or in memory.

CMP X0, #0

B.EQ JumpIfZeroLabel

ADD X1, X1, #1 @ This executes speculatively while B.EQ remains unresolved

The possible outcomes are shown in the picture below.

In the example above, the comparison is made on the X0 register. The next instruction creates a branch to the label. In the pipeline, while B.EQ instruction is being executed; the next instruction is already prepared to be executed, if not already (by speculation). When the branch outcome becomes known, the pipeline either commits the results (if the prediction was correct) or flushes the pipeline and re-fetches from the correct address (if the prediction was wrong). In such a way, if the register is not equal to zero, processor speculation wins in performance; otherwise, the third instruction result is discarded, and any microoperation for this instruction is cancelled—the processor branches to a new location.

From the architectural point of view, the speculations with instructions are invisible, as if those instructions never ran. But from a microarchitectural perspective (cache contents, predictors, buffers), all speculation leaves traces. Regarding registers, speculative updates remain in internal buffers until commit. No architectural changes happen until then. Regarding memory, speculative stores are not visible to other cores or devices and remain buffered until committed. But the speculative loads can occur. They may bring the data into cache memory even if it’s later discarded.

In this example, the AMR processor will perform speculative memory access:

LDR X0, [X1]

STR X2, [X3]

If the registers X1 and X3 are equal, the store may affect the load result. Processor instead of stalling until it knows for sure it will speculatively issue the load. The processor performs loads earlier to hide memory latency and keep execution units busy. The X1 register result may not be known for sure, since previous instructions may have computed it. If aliasing is later detected, the load result is discarded and reissued, a process called speculative load execution. It’s one of the primary sources of side-channel leaks (Spectre-class vulnerabilities) because speculative loads can cache data from locations the program shouldn’t have access to.