Table of Contents

Authors

MultiASM Consortium Partners proudly present the Assembler Programming Book, in its first edition. ITT Group

- Raivo Sell, Ph. D., ING-PAED IGIP

Riga Technical University

- Agris Nikitenko, Ph. D., Eng.

- Karlis Berkolds, M. sc., Eng.

- Eriks Klavins, M. sc., Eng.

Silesian University of Technology

- Piotr Czekalski, Ph. D., Eng.

- Krzysztof Tokarz, Ph. D., Eng.

- Godlove Suila Kuaban, Ph. D., Eng.

Western Norway University of Applied Sciences

- [mfojcik]Add data

Preface

This book is intended to provide comprehensive information about low-level programming in the assembler language for a wide range of computer systems, including:

- embedded systems - constrained devices,

- mobile and mobile-like devices - based on ARM architecture,

- PCs and servers - based on Intel and AMD x86 and in particular 64-bit (x86_64) architecture.

The book also contains an introductory chapter on general computer architectures and their components.

While low-level assembler programming was once considered outdated, it is now back, and this is because of the need for efficient and compact code to save energy and resources, thus promoting a green approach to programming. It is also essential for cutting-edge algorithms that require high performance while using constrained resources. Assembler is a base for all other programming languages and hardware platforms, and so is needed when developing new hardware, compilers and tools. It is crucial, in particular, in the context of the announced switch from chip manufacturing in Asia towards EU-based technologies.

We (the Authors) assume that persons willing to study this content possess some general knowledge about IT technologies, e.g., understand what an embedded system is and the essential components of computer systems, such as RAM, CPU, DMA, I/O, and interrupts and knows the general concept of software development with programming languages, C/C++ best (but not obligatory).

Project Information

This content was implemented under the following project:

- Cooperation Partnerships in higher education, 2023, MultiASM: A novel approach for energy-efficient, high performance and compact programming for next-generation EU software engineers: 2023-1-PL01-KA220-HED-000152401.

Consortium Partners

- Silesian University of Technology, Gliwice, Poland (Coordinator),

- Riga Technical University, Riga, Latvia,

- Western Norway University, Forde, Norway,

- ITT Group, Tallinn, Estonia.

Erasmus+ Disclaimer

This project has been co-funded by the European Union.

Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author or authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the Foundation for the Development of the Education System. Neither the European Union nor the entity providing the grant can be held responsible for them.

Copyright Notice

This content was created by the MultiASM Consortium 2023–2026.

The content is copyrighted and distributed under CC BY-NC Creative Commons Licence and is free for non-commercial use.

In case of commercial use, please get in touch with MultiASM Consortium representative.

Introduction

The old, somehow abandoned Assembler programming comes to light again: “machine code to machine code and assembler to the assembler.” In the context of rebasing electronics, particularly developing new CPUs in Europe, engineers and software developers need to familiarise themselves with this niche, still omnipresent technology: every code you write, compile, and execute goes directly or indirectly to the machine code.

Besides developing new products and the related need for compilers and tools, the assembler language is essential to generating compact, rapid implementations of algorithms: it gives software developers a powerful tool of absolute control over the hardware, mainly the CPU. To put it a bit tongue-in-cheek, you never know what the future holds. If the machines take over, we should at least speak their language.

Assembler programming applies to the selected and specific groups of tasks and algorithms.

Using pure assembler to implement, e.g., a user interface, is possible but does not make sense.

Nowadays, assembler programming is commonly integrated with high-level languages, and it is a part of the application's code responsible for rapid and efficient data processing without higher-level language overheads. This applies even to applications that do not run directly on the hardware but rather use virtual environments and frameworks (either interpreted or hybrid) such as Java, .NET languages, and Python.

It is a rule of thumb that the simpler and more constrained the device is, the closer the developer is to the hardware. An excellent example of this rule is development for an ESP32 chip: it has 2 cores that can easily handle Python apps, but when it comes to its energy-saving modes when only ultra-low power coprocessor is running, the only programming language available is assembler, it is compact enough to run in very constrained environments, using microampers of current and fitting dozen of bytes.

This book is divided into four main chapters:

- The first chapter introduces students to computer platforms and their architectures. Assembler programming is very close to the hardware, and understanding those concepts is necessary to write code successfully and effectively.

- The second chapter discusses programming in assemblers for constrained devices that usually do not have operating systems but are bare-metal programmed. As it is impossible to review all assemblers and platforms, the one discussed in detail in this chapter is the most popular: AVR (ATMEL) microcontrollers (e.g. Arduino Uno development board).

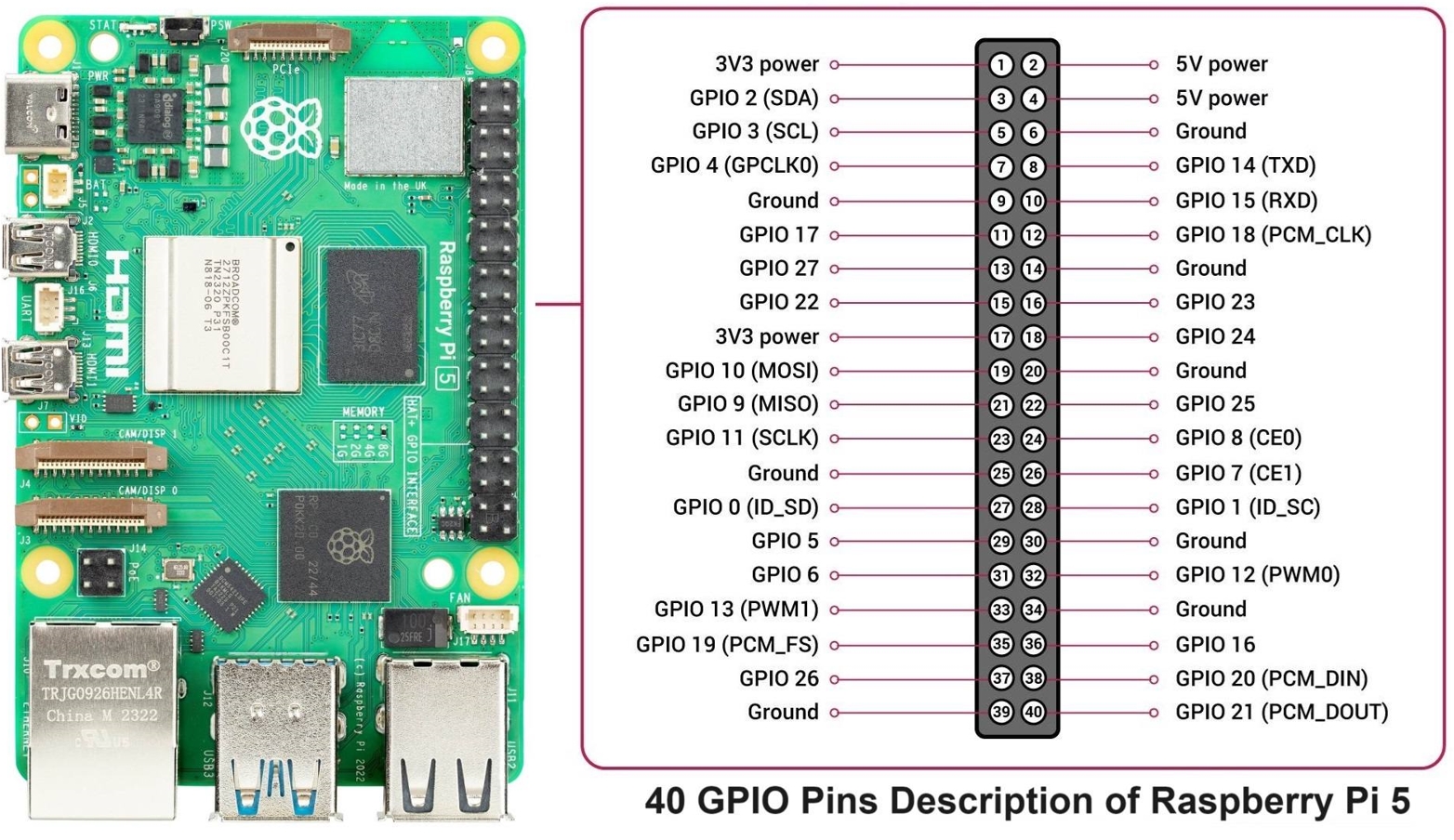

- The third chapter discusses assembler programming for the future of most devices: ARM architecture. This architecture is perhaps the most popular worldwide as it applies to mobile phones, edge and fog-class devices, and recently to the growing number of implementations in notebooks, desktops, and even workstations (e.g., Apple's M series). Practical examples use Raspberry Pi version 5.

- The last, fourth chapter describes in-depth assembler programming for PCs in its 64-bit version for Intel and AMD CPUs, including their CISC capabilities, such as SIMD instruction sets and their applications. Practical examples present (among others) the merging of the assembler code with .NET frontends under Windows.

The following chapters present the contents of the coursebook:

Computer Architectures

Assembler programming is a very low-level technique for writing the software. It uses the hardware directly relying on the architecture of the processor and computer with the possibility of having influence on every single element and every single bit in hundreds of registers which control the behaviour of the computer and all its units. That gives the programming engineer much more control over the hardware but also requires a high level of carefulness while writing programs. Modification of a single bit can completely change the way of a computer’s behaviour. This is why we begin our book on the assembler with a chapter about the architecture of computers. It is essential to understand how the computer is designed, how it operates, executes the programs, and performs calculations. It is worth mentioning that this is important not only for programming in assembler. The knowledge of computer and processor architecture is useful for everyone who writes the software in any language. Having this knowledge programming engineers can write more efficient applications in terms of memory use, time of execution and energy consumption.

You can notice that in this book we often use the term processor for elements sometimes called in some other way. Historically the processor or microprocessor is the element that represents the central processing unit (CPU) only and requires also memory and peripherals to form the fully functional computer. If the integrated circuit contains all mentioned elements it is called a one-chip computer or microcontroller. A more advanced microcontroller for use in embedded systems is called an embedded processor. An embedded processor which contains other modules, for example, a wireless networking radio module is called a System on Chip (SoC). From the perspective of an assembler programmer differentiating between these elements is not so important, and in current literature, all such elements are often called the processor. That's why we decided to use the common name “processor” although other names can also appear in the text.

Overall View on Computer Architecture: Processor, Memory, IO, Buses

The computers we use every day are all designed around the same general idea of cooperation among three base elements: processor, memory and peripheral devices. Their names represent their functions in the system: memory stores data and program code, the processor manipulates data by executing programs, and peripherals maintain contact with the user, the environment and other systems. To exchange information, these elements communicate through interconnections named buses. The generic block schematic diagram of the exemplary computer is shown in Fig. 2.

Processor

It is often called “the brain” of the computer. Although it doesn’t think, the processor is the element which controls all other units of the computer. The processor is the device that manages everything in the machine. Every hardware part of the computer is controlled more or less by the main processor. Even if the device has its own processor - for example, a keyboard - it works under the control of the main one. The processor handles events. We can say that synchronous events are those that the processor handles periodically. The processor can’t stop. Of course, when it has the power, even when you don’t see anything special happening on the screen. In PC computer in an operating system without a graphical user interface, for example, plain Linux, or a command box in Windows, if you see only „C:\>”, the processor works. In this situation, it executes the main loop of the system. In such a loop, it’s waiting for the asynchronous events. Such an asynchronous event occurs when the user pushes a key or moves the mouse, when the sound card stops playing a sound, or when the hard disk ends up transmitting the data. For all of those actions, the processor handles executing the programs - or, if you prefer, procedures.

A processor is characterised by its main parameters, including its operating frequency and class.

Frequency is crucial information which tells the user how many operations can be executed in a time unit. To have the detailed information of a real number of instructions per second, it must be combined with the average number of clock pulses required to execute the instruction. Older processors required a few or even a dozen clock pulses per instruction. Modern machines, thanks to parallel execution, can achieve impressive results of a few instructions per single cycle.

The processor's class indicates the number of bits in the data word. It tells us what the size of the arguments the processor can calculate with a single arithmetic, logic or other operation. The still-popular 8-bit machines have a data length of 8 bits, while the most sophisticated can use 32 or 64-bit arguments. The processor's class determines the size of its internal data registers, the size of instructions' arguments and the number of data bus lines.

Memory

Memory is the element of the computer that stores data and programs. It is visible to the processor as a sequence of data words, where every word has its own address. Addressing allows the processor to access simple and complex variables and to read the instructions for execution. Although intuitively, the size of a memory word should correspond to the class of the processor, it is not always true. For example, in PCs, independently of the processor class, the memory is always organised as a sequence of bytes and the size of it is provided in megabytes or gigabytes.

The size of the memory installed on the computer does not have to correspond to the size of the address space, the maximal size of the memory which is addressable by the processor. In modern machines, it would be impossible or hardly achievable. For example, for x64 architecture, the theoretical address space is 2^64 (16 exabytes). Even the address space currently supported by processors' hardware is as large as 2^48, which equals 256 terabytes. On the opposite side, in constrained devices, the size of the physical memory can be bigger than supported by the processor. To enable access to a bigger memory than the addressing space of the processor or to support flexible placement of programs in a big address space, the paging mechanism is used. It is a hardware support unit for mapping the address used by the processor into the physical memory installed in the computer.

Peripherals

Called also input-output (I/O) devices. There is a variety of units belonging to this group. It includes timers, communication ports, general-purpose inputs and outputs, displays, network controllers, video and audio modules, data storage controllers and many others. The main function of peripheral modules is to exchange information between the computer and the user, collect information from the environment, send and receive data to and from elements of the computer not connected directly to the processor, and exchange data with other computers and systems. Some of them are used to connect the processor to the functional unit of the same computer. For example, the hard disk drive is not connected directly to the processor. It uses the specialised controller, which is the peripheral module operating as an interface between the central elements of the computer and the hard drive. Another example can be the display. It uses a graphics card, which plays the role of a peripheral interface between the computer and the monitor.

Buses

The processor, memory and peripherals exchange information using interconnections called buses. Although you can find in the literature and on the internet a variety of bus types and their names, at the very lowest level, there are three buses connecting the processor, memory, and peripherals.

Address bus delivers the address generated by the processor to memory or peripherals. This address specifies the single memory cell or peripheral register that the processor wants to access. The address bus is used not only to address the data which the processor wants to transmit to or from memory or a peripheral. Instructions are also stored in memory, so the address bus also selects the instruction that the processor fetches and later executes. The address bus is one-directional. The address is generated by the processor and delivered to other units.

The number of lines in the address bus is fixed for the processor and determines the size of the addressing space the processor can access. For example, if the address bus of some processor has 16 lines, it can generate up to 16^2 = 65536 different addresses.

Data bus is used to exchange data between the processor and the memory or peripherals. The processor can read the data from memory or peripherals, or write the data to these units, previously sending their address with the address bus. As data can be read or written, the data bus is bi-directional.

The number of bits of the data bus usually corresponds to the class of the processor. It means that an 8-bit class processor has 8 lines of the data bus.

Control bus is formed by lines mainly used for synchronisation between the elements of the computer. In the minimal implementation, it includes the read and write lines. Read line (#RD) is the information to other elements that the processor wants to read the data from the unit. In such a situation, the element, e.g. memory, puts the data from the addressed cell on the data bus. Active write signal (#WR) informs the element that the data which is present on the data bus should be stored at the specified address. The control bus can also include other signals specific to the system, e.g. interrupt signals, DMA control lines, clock pulses, signals distinguishing the memory and peripheral access, signals activating chosen modules and others.

Von Neumann vs Harvard Architectures, Mixed Architectures

The classical architecture of computers uses a single address and a single data bus to connect the processor, memory and peripherals. This architecture is called von Neumann or Princeton, and we showed it in Fig. 3. Additionally, in this architecture, the memory contains the code of programs and the data they use. This suffers the drawback of the impossibility of accessing the instruction of the program and the data to be processed at the same time, called the von Neumann bottleneck. The answer to this issue is the Harvard architecture, where program memory is separated from the data memory, and they are connected to the processor with two pairs of address and data buses. Of course, the processor must support such a type of architecture. The Harvard architecture we show in Fig. 4.

Harvard architecture is very often used in one-chip computers. It does not suffer from the von Neumann bottleneck and additionally makes it possible to implement different lengths of the data word and instruction word. For example, the AVR 8-bit class family of microcontrollers has 16 bits of the program word. PIC microcontrollers, also 8-bit class, have 13 or 14-bit instruction word length. In modern microcontrollers, the program is usually stored in internal flash reprogrammable memory, and data in internal static RAM memory. All interconnections, including address and data buses, are implemented internally, making the implementation of the Harvard architecture easier than in a computer based on the microprocessor. In several mature microcontrollers, the program and data memory are separated but connected to the processor unit with a single set of buses. It is named mixed architecture. This architecture benefits from an enlargement of the size of the possible address space, but still suffers from the von Neumann bottleneck. This approach can be found in the 8051 family of microcontrollers. The schematic diagram of mixed architecture we presented in Fig. 5.

CISC, RISC

It is not only the whole computer that can have a different architecture. This also touches processors. There are two main internal processor architectures: CISC and RISC. CISC stands for Complex Instruction Set Computer, while RISC stands for Reduced Instruction Set Computer. The naming difference can be a little confusing because it treats the instruction set as complex or reduced. We can find CISC and RISC processors with a similar number of instructions implemented. The difference is rather in the complexity of instructions, not just the instruction set.

Complex instructions mean that a typical single CISC processor instruction performs more operations during its execution than a typical RISC instruction. The CISC processors also implement more sophisticated addressing modes. This means that if we want to implement an algorithm, we can use fewer CISC instructions compared to more RISC instructions. Of course, it comes with the price of a more sophisticated construction of a CISC processor than RISC. The complexity of a circuit influences the average execution time of a single instruction. As a result, the CISC processor does more work during program execution, while in RISC, the compiler (or assembler programmer) does more work during the implementation phase.

The most visible distinguishing features between RISC and CISC architectures to a programmer lie in the general-purpose registers and instruction operands. Typically, in CISC, the number of registers is smaller than in RISC. Additionally, they are specialised. It means that not all operations can be performed using any register. For example, in some CISC processors, arithmetic calculations can be done only with the use of a special register called the accumulator, while addressing of a table element or using a pointer can be done with the use of a special index (or base) register. In RISC, almost all registers can be used for any purpose, like the mentioned calculations or addressing. In CISC processors, instructions usually have two arguments in the form of:

operation arg1, arg2 ; Example: arg1 = arg1 + arg2

In such a situation, arg1 is one of the sources and also a destination - the place for the result. It destroys the original arg1 value. In many RISC processors, three-argument instructions are present:

operation arg1, arg2, arg3 ; Example: arg3 = arg1 + arg2

In such an approach, two arguments are the source, and the third one is the destination - original arguments are preserved and can be used for further calculations. The table 1 summarises the difference between CISC and RISC processors.

| Feature | CISC | RISC |

|---|---|---|

| Instructions | Complex | Simple |

| Registers | Specialised | Universal |

| Number of registers | Smaller | Larger |

| Calculations | With accumulator | With any register |

| Addressing modes | Complex | Simple |

| Non destroying instructions | No | Yes |

| Examples of processors | 8086, 8051 | AVR, ARM |

All these features make the RISC architecture more flexible, allowing the programmer or compiler to create code without unnecessary data transfer. The execution units of RISC processors can be simpler in construction, enabling higher operating frequencies and faster program execution. What is interesting is that the modern versions of popular CISC machines, such as Intel and AMD processors used in personal computers, internally translate CISC instructions into RISC microoperations, which are executed by execution units. A simple instruction can be converted directly into a single microoperation. Complex instructions are often implemented as sequences of microoperations called microcodes.

Components of Processor: Registers, ALU, Bus Control, Instruction Decoder

From our perspective, the processor is the electronic integrated circuit that controls other elements of the computer. Its main ability is to execute instructions. While we will go into details of the instruction set, you will see that some instructions perform calculations or process data, while others do not. This suggests that the processor comprises two main units. One of them is responsible for instruction execution, while the second performs data processing. The first one is called the control unit or instruction processor. The second one is named the execution unit or data processor. We can see them in Fig 6.

Control unit

The function of the control unit, also known as the instruction processor, is to fetch, decode and execute instructions. It also generates signals to the execution unit if the instruction being executed requires so. It is a synchronous and sequential unit. Synchronous means that it changes state synchronously with the clock signal. Sequential means that the next state depends on the states at the inputs and the current internal state. As inputs, we can consider not only physical signals from other units of the computer but also the code of the instruction. To ensure that the computer behaves the same every time it is powered on, the execution unit is set to the known state at the beginning of operation by the RESET signal. A typical control unit contains some essential elements:

- Instruction register (IR).

- Instruction decoder.

- Program counter (PC)/instruction pointer (IP).

- Stack pointer (SP).

- Bus interface unit.

- Interrupt controller.

Elements of the control unit are shown in Fig 7.

The control unit executes instructions in a few steps:

- Generates the address of the instruction.

- Fetches instruction code from memory.

- Decodes instructions.

- Generates signals to the execution unit or executes instructions internally.

In detail, the process looks as follows:

- The control unit takes the address of the instruction to be executed from a special register known as the Instruction Pointer or Program Counter and sends it to the memory via the address bus. It also generates signals on the control bus to synchronise memory with the processor.

- Memory takes the code of instruction from the provided address and sends it to the processor using a data bus.

- The processor stores the instruction code in the instruction register and, based on the bit pattern, interprets what to do next.

- If the instruction requires the execution unit operation, the control unit generates signals to control it. In cooperation with the execution unit, it can also read data from or write data to the memory.

The control unit works according to the clock signal generator cycles known as main clock cycles. With every clock cycle, some internal operations are performed. One such operation is reading or writing the memory, which sometimes requires more than a single clock cycle. Single memory access is known as a machine cycle. As instruction execution sometimes requires more than one memory access and other actions, the execution of the whole instruction is named an instruction cycle. Summarising, one instruction execution requires one instruction cycle and several machine cycles, each composed of a few main clock cycles. Modern advanced processors are designed in such a way that they are able to execute a single instruction (sometimes even more than one) every single clock cycle. This requires a more complex design of a control unit, many execution units and other advanced techniques, which makes it possible to process more than one instruction at a time.

The control unit also accepts input signals from peripherals, enabling interrupts and direct memory access mechanisms. For proper return from the interrupt subroutine, the control unit uses a special register called the stack pointer. Interrupts and direct memory access mechanisms will be explained in detail in further chapters.

Execution unit

An execution unit, also known as the data processor, executes instructions. Typically, it is composed of a few essential elements:

- Arithmetic logic unit (ALU).

- Accumulator and set of registers,

- Flags register,

- Temporal register.

The arithmetic logic unit (ALU) is the element that performs logical and arithmetical calculations. It uses data coming from registers, the accumulator or from memory. Data coming from memory for arithmetic and logic instructions is stored in the temporal register. The result of calculations is stored back in the accumulator, another register or memory. In some legacy CISC processors, the only possible place for storing the result is the accumulator. Besides the result, ALU also returns some additional information about the calculations. It modifies the bits in the flag register, which comprises flags that are modified according to the results from arithmetic and logical operations. For example, if the result of the addition operation is too large to be stored in the resulting argument, the carry flag is set to indicate such a situation.

Typically, the flags register includes:

- Carry flag, set in case a carry or borrow occurs.

- Sign flag, indicating whether the result is negative.

- Zero flag, set in case the result is zero.

- Auxiliary Carry flag used in BCD operations.

- Parity flag, which indicates whether the result has an even number of ones.

The flags are used as conditions for decision-making instructions (like if statements in some high-level languages). The flags register can also implement some control flags to enable/disable processor functionalities. An example of such a flag can be the Interrupt Enable flag from the 8086 microprocessor.

Registers

Registers are memory elements which are placed logically and physically very close to the arithmetic logic unit. It makes them the fastest memory in the whole computer. They are sometimes called scratch registers, and the set of registers is called the register file.

As we mentioned in the chapter about CISC and RISC processors, in CISC processors, registers are specialised, including the accumulator. A typical CISC execution unit is shown in Fig 8.

A typical RISC execution unit does not have a specialised accumulator register. It implements the set of scratch registers as shown in Fig 9.

Processor Taxonomies, SISD, SIMD, MIMD

As we already know, the processor executes instructions which can process the data. We can consider two streams flowing through the processor. A stream of instructions which passes through the control unit, and a stream of data processed by the execution unit. In 1966, Michael Flynn proposed the taxonomies to define different processors' architectures. Flynn classification is based on the number of concurrent instruction (or control) streams and data streams available in the architecture. Taxonomies as proposed by Flynn are presented in Table2

| Basic taxonomies | Data streams | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Single | Multiple | ||

| Instruction streams | Single | SISD | SIMD |

| Multiple | MISD | MIMD | |

SISD

Single Instruction Single Data processor is a classical processor with a single control unit and a single execution unit. It can fetch a single instruction in one cycle and perform a single calculation. Mature PC computers based on 8086, 80286 or 80386 processors or some modern small-scale microcontrollers like AVR, are examples of such an architecture.

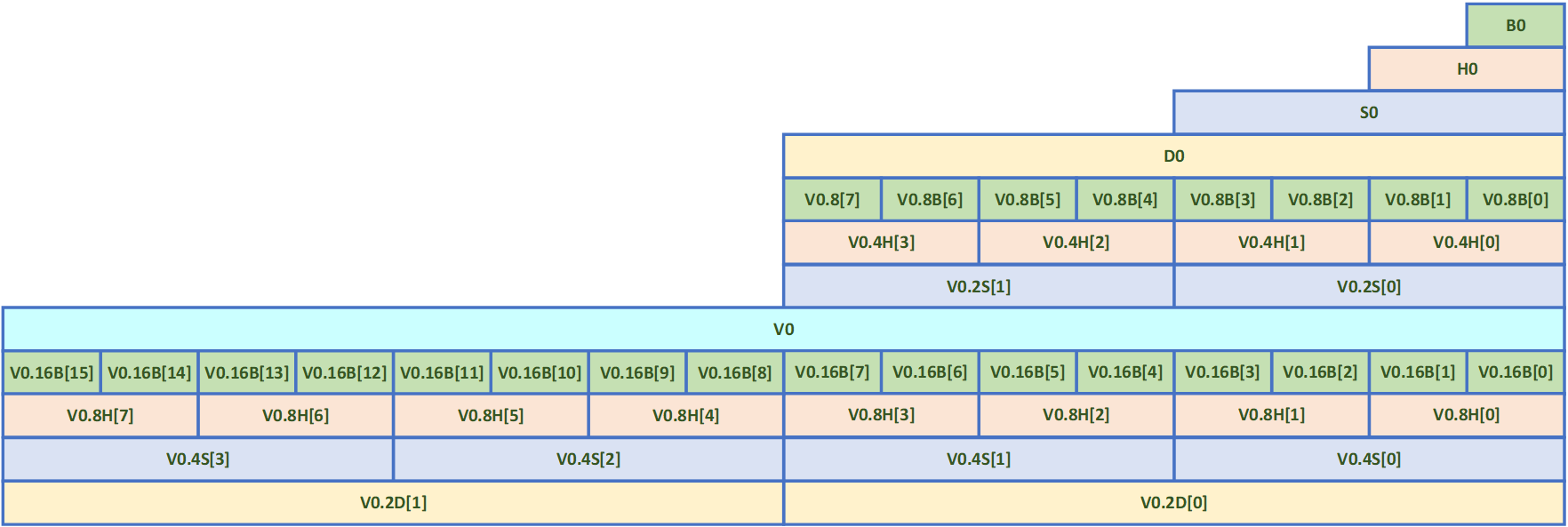

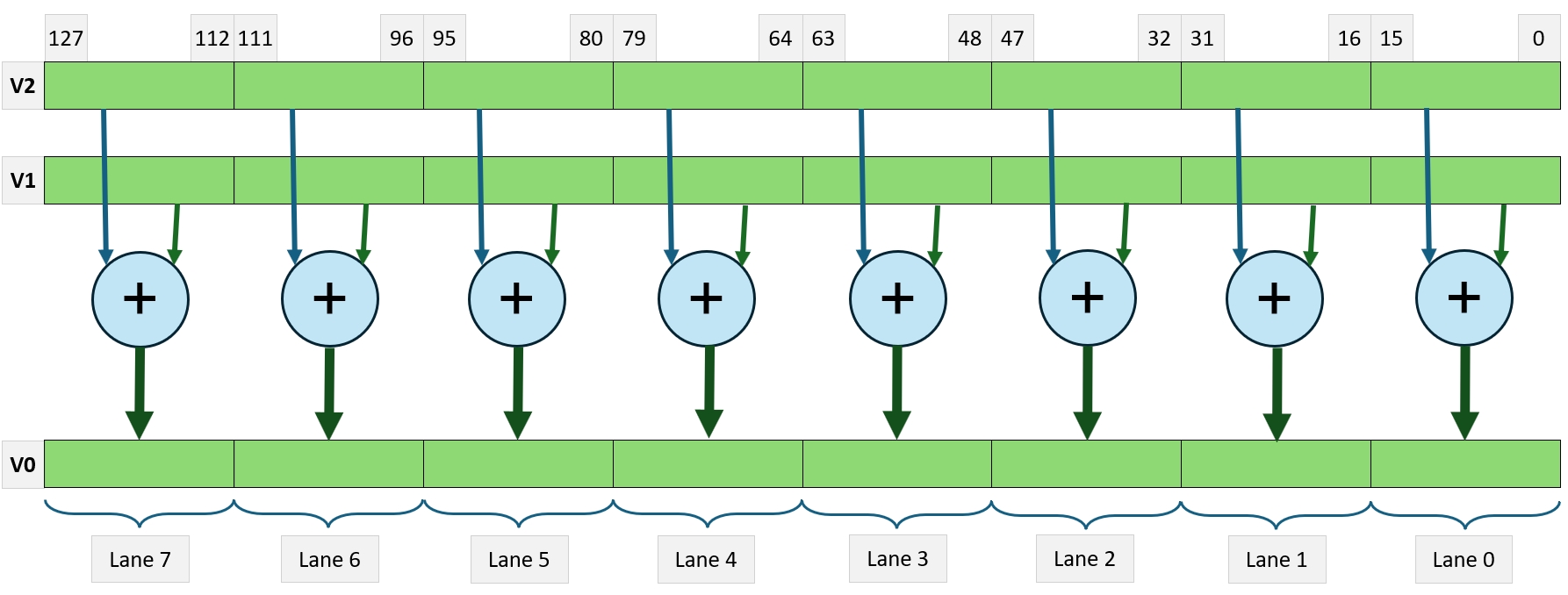

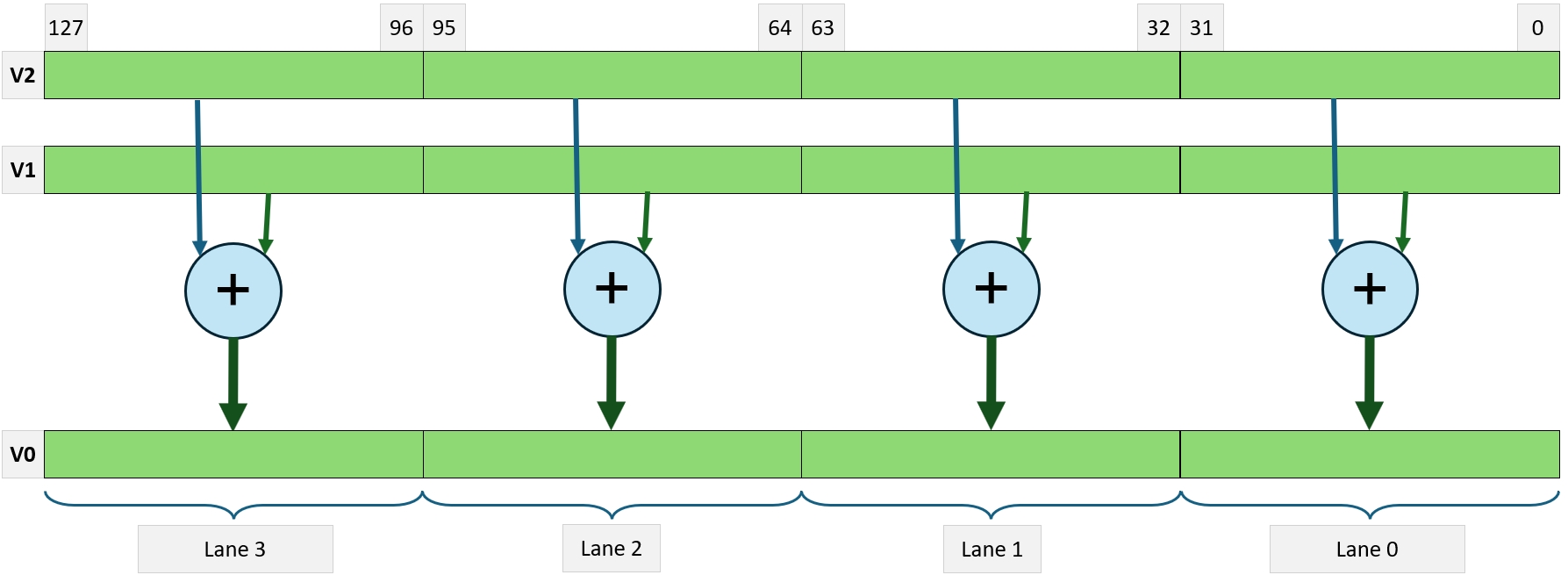

SIMD

Single Instruction Multiple Data is an architecture in which one instruction stream can perform calculations on multiple data streams. Good examples of implementation of such architecture are all vector instructions (called also SIMD instructions) like MMX, SSE, AVX, and 3D-Now in x64 Intel and AMD processors. Modern ARM processors also implement SIMD instructions, which perform vectorised operations.

MIMD

Multiple Instruction Multiple Data is an architecture in which many control units operate on multiple streams of data. These are all architectures with more than one processor (multi-processor architectures). MIMD architectures include multi-core processors like modern x64, ARM and even ESP32 SoCs. This also includes supercomputers and distributed systems, using common shared memory or even a distributed but shared memory.

MISD

Multiple Instruction Single Data. At first glance, it seems illogical, but these are machines where the certainty of correct calculations is crucial and required for the security of the system operation. Such an approach can be found in applications like space shuttle computers.

SIMT

Single Instruction Multiple Threads. Originally defined as the subset of SIMD. The difference between SIMD and SIMT is that in pure SIMD, a single instruction operates on all elements of the vector in the same way. In SIMT, selected threads can be activated or deactivated. Instructions and data are processed only on the active threads, while the data remains unchanged on inactive threads.

We can find SIMT in modern constructions. Nvidia uses this execution model in their G80 architecture [1], where multiple independent threads execute concurrently using a single instruction. In x64 architecture, the new vector instructions have masked variants, in which an operation can be turned on or off for selected vector elements. This is done by an additional operand called a mask or predicates.

Memory, Types and Their Functions

The computer cannot work without memory. The processor fetches instructions from memory, and data is also stored there. In this chapter, we will discuss memory types, technologies and their properties. The overall view of computer memory can be represented by the memory hierarchy triangle shown in Fig. 10, where the available size reduces while going up, but the access time decreases significantly. It is visible that the fastest memory in the computer is the set of internal registers, next is the cache memory, operational memory (RAM), disk drive, and the slowest, but the largest is the memory available via the computer network - usually the Internet.

In the table 3, you can find the comparison of different memory types with their estimated size and access time.

| Memory type | Average size | Access time |

|---|---|---|

| Registers | few kilobytes | <1 ns |

| Cache | few megabytes | <10 ns |

| RAM | few gigabytes | <100 ns |

| Disk | few terabytes | <100 us |

| Network | unlimited | a few seconds, but can be unpredictable |

Address space

Before we start talking about details of memory, we will mention the term address space. The processor can access instructions of the program and data to process. The question is how many instructions and data elements it can reach? The possible number of elements (usually bytes) represents the address space available for the program and for data. We know from the chapter about von Neumann and Harvard architectures that these spaces can overlap or be separate.

The size of the program address space is determined by the number of bits of the Instruction Pointer register. In many 8-bit microprocessors, the size of IP is 16 bits. It means that the size of the address space, expressed in the number of distinct addresses the processor can reach, is 2^16 = 65536 (64k). It is too small for bigger machines like personal computers, so here the number of bits of IP is 64 (although the actual number of bits used is limited to 48).

The size of the possible data address space is determined by addressing modes and the size of index registers used for indirect addressing. In 8-bit microprocessors, it is sometimes possible to join two 8-bit registers to achieve an address space of the same 64k size as for the program. In personal computers, the program and data address spaces overlap, so the data address space is the same as the program address space.

Program memory

In this kind of memory, the instructions of the programs are stored. In many computers (like PCs), the same physical memory is used to store the program and the data. This is not the case in most microcontrollers, where the program is stored in non-volatile memory, usually Flash EEPROM. Even if the memory for programs and data is common, the code area is often protected from writing to prevent malware and other viruses from interfering with the original, safe software.

Data memory

In data memory, all kinds of data can be stored. Here we can find numbers, tables, pictures, audio samples and everything that is processed by the software. Usually, the data memory is implemented as RAM, with the possibility of reading and writing. RAM is a volatile memory, so its content is lost if the computer is powered off.

Memory technologies

There are different technologies for creating memory elements. The technology determines if memory is volatile or non-volatile, the physical size (area) of a single bit, the power consumption of the memory array, and how fast we can access the data. According to the data retention, we can divide memories into two groups:

- non-volatile,

- volatile.

Non-volatile memories are implemented as:

- ROM

- PROM

- EPROM

- EEPROM

- Flash EEPROM

- FRAM

Volatile memories have two main technologies:

- Static RAM

- Dynamic RAM

Non-volatile memories

Non-volatile memories are used to store the data which should be preserved during the power is off. Their main application is to store the code of the program, constant data tables, and parameters of the computer (e.g. network credentials). The hard disk drive (or SSD) is also a non-volatile memory, although not directly accessible by the processor via address and data buses.

ROM

ROM - Read Only Memory is the kind of memory that is programmed by the chip manufacturer during the production of the chip. This memory has fixed content which can't be changed in any way. It was popular as a program memory in microcontrollers a few years ago because of the low price of a single chip, but due to the need for replacement of the whole chip in case of an error in the software and lack of possibility of a software update, it was replaced with technologies which allow reprogramming the memory content. Currently, ROM is sometimes used to store the serial number of a chip.

PROM

PROM - Programmable Read Only Memory is the kind of memory that can be programmed by the user but can't be reprogrammed further. It is sometimes called OTP - One Time Programming. Some microcontrollers implement such a memory, but due to the inability of software updates, it is a choice for simple devices with a short product lifetime. OTP technology is used in some protection mechanisms for protecting from unauthorised software change or reconfiguration of the device.

EPROM

EPROM - Erasable Programmable Read Only Memory is a memory which can be erased and programmed many times. The data can be erased by shining an intense ultraviolet light through a special glass window into the memory chip for a few minutes. After erasing, the chip can be programmed again. This kind of memory was very popular a few years ago, but due to a complicated erase procedure, requiring a UV light source, it was replaced with EEPROM.

EEPROM

EEPROM - Electrically Erasable Programmable Read Only Memory is a type of non-volatile memory that can be erased and reprogrammed many times with electric signals only. They replaced EPROM memories due to ease of use and the possibility of reprogramming without removing the chip from the device. It is designed as an array of MOSFET transistors with so-called floating gates, which can be charged or discharged and keep the stable state for a long time (at least 10 years). In EEPROM memory, every byte can be individually reprogrammed.

Flash EEPROM

Flash EEPROM is a type of non-volatile memory that is similar to EEPROM. Whilst in the EEPROM, a single byte can be erased and reprogrammed, in the Flash version, erasing is possible in larger blocks. This reduces the area occupied by the memory, making it possible to create denser memories with larger capacity. Flash memories can be realised as part of a larger chip, making it possible to design microcontrollers with built-in reprogrammable memory for the firmware. This enables firmware updates without the need for any additional tools or removing the processor from the operating device. It also allows remote firmware updates.

FRAM

FRAM - Ferroelectric Random Access Memory is a type of memory where the information is stored with the effect of a change of polarity of ferroelectric material. The main advantage is that the power efficiency, access time, and density are comparable to DRAM, but without the need for refreshing and with data retention while the power is off. The main drawback is the price, which limits the popularity of FRAM applications. Currently, due to their high reliability, FRAMs are mainly used in specialised applications like data loggers, medical equipment, and automotive “black boxes”.

Volatile memories

Volatile memory is used for temporal data storage while the computer system is running. Their content is lost after the power is off. Their main application is to store the data while the program processes it. Their main applications are operational memory (known as RAM), cache memory, and data buffers.

SRAM

SRAM - Static Random Access Memory is the memory used as operational memory in smaller computer systems and as cache memory in larger machines. Its main benefit is very high operational speed. The access time can be as short as a few nanoseconds, making it the first choice when speed is required: in cache memory or as the processor's registers. The drawbacks are the area and power consumption. Every bit of static memory is implemented as a flip-flop and composed of six transistors. Due to its construction, the flip-flop always consumes some power. That is the reason why the capacity of SRAM memory is usually limited to a few hundred kilobytes, up to a few megabytes.

DRAM

DRAM - Dynamic Random Access Memory is the memory used as operational memory in bigger computer systems. Its main benefit is very high density. The information is stored as a charge in a capacitance created under the MOSFET transistor. Because every bit is implemented as a single transistor, it is possible to implement a few gigabytes in a small area. Another benefit is the reduced power required to store the data in comparison to static memory. But there are also drawbacks. DRAM memory is slower than SRAM. The addressing method and the complex internal construction prolong the access time. Additionally, because the capacitors which store the data discharge in a short time, DRAM memory requires refreshing, typically 16 times per second; it is done automatically by the memory chip, but additionally slows the access time.

Peripherals

Peripherals or peripheral devices, also known as Input-Output devices, enable the computer to remain in contact with the external environment or expand the computer's functionality. Peripheral devices enhance the computer's capability by making it possible to enter information into a computer for storage or processing and to deliver the processed data to a user, another computer, or a device controlled by the computer. Internal peripherals are connected directly to the address, data, and control buses of the computer. External peripherals can be connected to the computer via USB or a similar connection.

Types of peripherals

There is a variety of peripherals which can be connected to the computer. The most commonly used are:

- parallel input/output ports

- serial communication ports

- timers/counters

- analogue to digital converters

- digital to analogue converters

- interrupt controllers

- DMA controllers

- displays

- keyboards

- sensors

- actuators

Addressing of I/O devices

From the assembler programmer's perspective, the peripheral device is represented as a set of registers available in the I/O address space. Registers of peripherals are used to control their behaviour, including mode of operation, parameters, configuration, speed of transmission, etc. Registers are also data exchange points where the processor can store data to be transmitted to the user or external computer, or read the data coming from the user or another system.

The size of the I/O address space is usually smaller than the size of the program or data address space. The method of accessing peripherals depends on the design of the processor. We can find two methods of I/O addressing implementation: separate or memory-mapped I/O.

Separate I/O address space

A separate I/O address space is accessed independently of the program or data memory. In the processor, it is implemented with the use of separate control bus lines to read or write I/O devices. Separate control lines usually mean that the processor also implements different instructions to access memory and I/O devices. It also means that the chosen peripheral and byte in the memory can have the same address, and only the type of instruction used distinguishes the final destination of the address. Separate I/O address space is shown schematically in Fig 11. Reading the data from the memory is activated with the #MEMRD signal, writing with the #MEMWR signal. If the processor needs to read or write the register of the peripheral device, it uses #IORD or #IOWR lines, respectively.

Memory-mapped I/O address space

In this approach, the processor doesn't implement separate control signals to access the peripherals. It uses a #RD signal to read the data from and a #WR signal to write the data to a common address space. It also doesn't have different instructions to access registers in the I/O address space. Every such register is visible like any other memory location. It means that this is only the responsibility of the software to distinguish the I/O registers and data in the memory. Memory-mapped I/O address space is shown schematically in Fig 12.

Instruction Execution Process

As we already mentioned, instructions are executed by the processor in a few steps. You can find in the literature descriptions that there are three, four, or five stages of instruction execution. Everything depends on the level of detail one considers. The three-stage description says that there are fetch, decode and execute steps. The four-stage model says that there are fetch, decode, data read and execute steps. The five-stage version adds another final step for writing the result back and sometimes reverses the steps of data read and execution.

It is worth remembering that even a simple fetch step can be divided into a set of smaller actions which must be performed by the processor. The real execution of instructions depends on the processor's architecture, implementation and complexity. Considering the five-stage model, we can describe the general stages of instruction execution:

- Fetching the instruction:

- The processor addresses the instruction by sending the content of the IP register on the address bus.

- The processor reads the code of the instruction from program memory through the data bus.

- The processor stores the code of the instruction in the instruction register.

- The processor prepares the IP (possibly increments) to point to the next instruction in a stream.

- Instruction decoding:

- A simple instruction can be interpreted directly by the instruction decoder logic.

- More complex instructions are processed in some steps by microcodes.

- Results are provided to the execution unit.

- Data reading (if the instruction requires reading the data):

- The processor calculates the address of the data in the data memory.

- The processor sends this address by address bus to the memory.

- The processor reads the data from memory and stores it in the accumulator or general-purpose register.

- Instruction execution:

- The execution unit performs actions as encoded in the instruction (simple or with microcode).

- In modern processors, there are more execution units, and they can execute several instructions simultaneously.

- Writing back the result:

- The processor writes the result of calculations into the register or memory.

Instruction encoding

From the perspective of the processor, instructions are binary codes, unambiguously determining the activities that the processor is to perform. Instructions can be encoded using a fixed or variable number of bits.

A fixed number of bits makes the construction of the instruction decoder simpler because the choice of some specific behaviour or function of the execution unit is encoded with the bits, which are always at the same position in the instruction. On the opposite side, if the designer plans to expand the instruction set with new instructions in the future, there must be some spare bits in the instruction word reserved for future use. It makes the code of the program larger than required. Fixed lengths of instructions are often implemented in RISC machines. For example, in the ARM architecture, instructions have 32 bits. In AVR, instructions are encoded using 16 bits.

A variable number of bits makes the instruction decoder more complex. Based on the content of the first part of the instruction (usually a byte), it must be able to decide what is the length of the whole instruction. In such an approach, instructions can be as short as one byte or much longer. An example of a processor with variable instruction length is the 8086 and all further processors from the x86 and x64 families. Here, the instructions, including all possible constant arguments, can have even 15 bytes.

Modern Processors: Cache, Pipeline, Superscalar, Branch Prediction, Hyperthreading

Modern processors have a very complex design and include many units responsible mainly for shortening the execution time of the software.

Cache

Cache memory forms a layer in the memory hierarchy that intermediates between the main memory and the processor registers. The main reason for the introduction of cache memory is that main memory based on DRAM technology is much slower than the processor, which is based on static technology. The cache exploits two software features: spatial locality and temporal locality. Spatial locality results from the fact that the processor executes code, which in most cases is a sequence of instructions arranged directly behind each other. Temporal locality arises because programs often run in loops, repeatedly working on a single set of data over short intervals. In both cases, a larger fragment of a program or data can be loaded into the cache and operated on without having to access the main memory each time. Main memory is designed to significantly speed up reading and writing data in blocks compared to accessing random addresses. These properties allow a code fragment to be read in its entirety from main memory into the cache and executed without the need to access RAM for each instruction separately. In the case of data, the processor performs calculations after reading a block into the cache and then stores the results in a single write sequence.

In modern processors, the cache is divided into several levels, usually three. The first-level cache (L1) is the closest to the processor, the fastest, and is usually divided into separate instruction and data caches. The second-level cache (L2) is shared, slower and usually larger than the L1 cache. The largest and the slowest is the third-level cache (L3). It is closest to the computer's main memory. An average latency of L1 cache is 1-2 ns, L2 has a latency of 3-5 ns, and L3 about 10-20 ns. An example i7 processor, for each core, has 32 KB of L1 code cache, 32 KB of L1 data cache, and 256 KB of L2 cache for both code and data. The third-level cache (L3) is 8 MB and is shared by all cores.

Besides the size, important parameters of cache are the line length and associativity. Length of the line is usually expressed in bytes. It tells how many bytes are stored in a single, smallest possible data fragment. It also determines at what addresses such a data fragment starts in main memory. For example, if the cache line length is 64 bytes and memory is byte-organised, the block of memory copied to cache always starts at an address evenly divisible by 64. Associativity tells how many cache lines can be used to store the block from a specific address. If the block can go to any cache line, the cache is fully associative. If there is only one possible location, the cache is named direct-mapped. A fully associative cache is more flexible, but complex and expensive. Direct-mapped cache is simple, but it can cause data conflicts if two blocks of memory which should go to the same cache line need to be loaded. In real processors, the compromise solution is often implemented, which enables storing each block in 2, 4 or 8 different cache lines. It is named 2-, 4- or 8-way associative cache. This solution significantly reduces conflicts and ensures good performance at a reasonable cost.

Pipeline

As was described in the previous chapter, executing a single instruction requires many actions which must be performed by the processor. We could see that each step, or even substep, can be performed by a separate logical unit. This feature has been used by designers of modern processors to create a processor in which instructions are executed in a pipeline. A pipeline is a collection of logical units that execute many instructions at the same time - each of them at a different stage of execution. If the instructions arrive in a continuous stream, the pipeline allows the program to execute faster than a processor that does not support the pipeline. Note that the pipeline does not reduce the time of execution of a single instruction. It increases the throughput of the instruction stream.

A simple pipeline is implemented in AVR microcontrollers. It has two stages, which means that while one instruction is executed, another one is fetched as shown in Fig 13.

A mature 8086 processor executed the instruction in four steps. This allowed for the implementation of the 4-stage pipeline as shown in Fig. 14

Modern processors implement longer pipelines. For example, Pentium III used the 10-stage pipeline, Pentium 4 20-stage pipeline, and Pentium 4 Prescott even used a 31-stage pipeline. Does the longer pipeline mean faster program execution? Everything has benefits and drawbacks. The undoubted benefit of a longer pipeline is more instructions executed at the same time, which gives a higher instruction throughput. But the problem appears when branch instructions come. While a conditional jump appears in the instruction stream, the processor must choose which way the stream should follow. Should the jump be taken or not? The answer is usually based on the result of the preceding instruction and is known when the branch instruction is close to the end of the pipeline. In such a situation, in modern processors, the branch prediction unit guesses what to do with the branch. If it misses, the pipeline content is invalidated, and the pipeline starts operation from the beginning. This causes stalls in the program execution. If the pipeline is longer, the number of instructions to invalidate is bigger. In modern microarchitectures, the length of the pipeline varies between 12 and 20.

Superscalar

The superscalar processor increases the speed of program execution because it can execute more than a single instruction during a clock cycle. It is realised by simultaneously dispatching instructions to different execution units on the processor. The superscalar processor can, but doesn't have to, implement two or more independent pipelines. Rather, decoded instructions are sent for further processing to the chosen execution unit as shown in Fig. 15.

In the x86 family first processor with two paths of execution was the Pentium with two execution units called U and V. Modern x64 processors like i7 implement six execution units. Not all execution units have the same functionality. For example, in the i7 processor, every execution unit has different possibilities, as presented in table 4.

| Execution unit | Functionality |

|---|---|

| 0 | Integer calculations, Floating point multiplication, SSE multiplication, divide |

| 1 | Integer calculations, Floating point addition, SSE addition |

| 2 | Address generation, load |

| 3 | Address generation, store |

| 4 | Data store |

| 5 | Integer calculations, Branch, SSE addition |

Branch prediction

As it was mentioned, the pipeline can suffer invalidation if the conditional branch is not properly predicted. The branch prediction unit is used to guess the outcome of conditional branch instructions. It helps to reduce delays in program execution by predicting the path the program will take. Prediction is based on historical data and program execution patterns. There are many methods of predicting the branches. In general, the processor implements the buffer with the addresses of the last few branch instructions with a history register for every branch. Based on history, the branch prediction unit can guess if the branch should be taken.

Hyperthreading

Hyper-Threading Technology is an Intel approach to simultaneous multithreading technology, which allows the operating system to execute more than one thread on a single physical core. For each physical core, the operating system defines two logical processor cores and shares the load between them when possible. The hyperthreading technology uses a superscalar architecture to increase the number of instructions that operate in parallel in the pipeline on separate data. With Hyper-Threading, one physical core appears to the operating system as two separate processors. The logical processors share the execution resources, including the execution engine, caches, and system bus interface. Only the elements that store the architectural state of the processor are duplicated, including essential registers for code execution.

Fundamentals of Addressing Modes

Addressing Mode is the way in which the argument of an instruction is specified. The addressing mode defines a rule for interpreting the address field of the instruction before the operand is reached. Addressing mode is used in instructions which operate on the data or in instructions which change the program flow.

Data addressing

Instructions which reach the data have the possibility of specifying the data placement. The data is an argument of the instruction, sometimes called an operand. Operands can be of one of the following: register, immediate, direct memory, or indirect memory. As in this part of the book, the reader doesn't know any assembler instructions, we will use the hypothetical instruction copy that copies the data from the source operand to the destination operand. The order of the operands will be similar to high-level languages, where the left operand is the destination and the right operand is the source. Copying data from a to b will be done with an instruction as in the following example:

copy b, a

Register operand is used where the data which the processor wants to reach is stored or is intended to be stored in the register. If we assume that a and b are both registers named R0 and R1, the instruction for copying data from R0 to R1 will look as in the following example and as shown in the Fig.16.

copy R1, R0

An immediate operand is a constant or the result of a constant expression. The assembler encodes immediate values into the instruction at assembly time. The operand of this type can be only one in the instruction and is always at the source place in the operands list. Immediate operands are used to initialise the register or variable, as numbers for comparison. An immediate operand, as it's encoded in the instruction, is placed in code memory, not in data memory and can't be modified during software execution. Instruction which initialises register R1 with the constant (immediate) value of 5 looks like this:

copy R1, 5

A direct memory operand specifies the data at a given address. An address can be given in numerical form or as the name of the previously defined variable. It is equivalent to a static variable definition in high-level languages. If we assume that the var represents the address of the variable, the instruction which copies data from the variable to R1 can look like this:

copy R1, var

Indirect memory operand is accessed by specifying the name of the register whose value represents the address of the memory location to reach. We can compare the indirect addressing to the pointer in high-level languages, where the variable does not store the value but points to the memory location where the value is stored. Indirect addressing can also be used to access elements of the table in a loop, where we use the index value, which changes every loop iteration, rather than a single address. Different assemblers have different notations of indirect addressing; some use brackets, some square brackets, and others @ symbol. Even different assembler programs for the same processor can differ. In the following example, we assume the use of square brackets. The instruction which copies the data from the memory location addressed by the content of the R0 register to R1 register would look like this:

copy R1, [R0]

Variations of indirect addressing. The indirect addressing mode can have many variations where the final address doesn't have to be the content of a single register, but rather the sum of a constant value with one or more registers. Some variants implement automatic incrementation (similar to the “++” operator) or decrementation (“- -”) of the index register before or after instruction execution to make processing the tables faster. For example, accessing elements of the table where the base address of the table is named data_table and the register R0 holds the index of the byte which we want to copy from a table to R1 could look like this:

copy R1, table[R0]

Addressing mode with pre-decrementation (decrementing before instruction execution) could look like this:

copy R1, table[--R0]

Addressing mode with post-incrementation (incrementing after instruction execution) could look like this:

copy R1, table[R0++]

Program control flow destination addressing

The operand of jump, branch, or function call instructions addresses the destination of the program flow control. The result of these instructions is the change of the Instruction Pointer content. Jump instructions should be avoided in structural or object-oriented high-level languages, but they are rather common in assembler programming. Our examples will use the hypothetic jump instruction with a single operand—the destination address.

Direct addressing of the destination is similar to direct data addressing. It specifies the destination address as the constant value, usually represented by a name. In assembler, we define the names of the addresses in code as labels. In the following example, the code will jump to the label named destin:

jump destin

Indirect addressing of the destination uses the content of the register as the address where the program will jump. In the following example, the processor will jump to the destination address, which is stored in R0:

jump [R0]

Absolute and Relative addressing

In all previous examples, the addresses were specified as the values which represent the absolute memory location. The resulting address (even calculated as the sum of some values) was the memory location counted from the beginning of the memory, address “0”. It is presented in Fig23.

Absolute addressing is simple and doesn't require any additional calculations by the processor. It is often used in embedded systems, where the software is installed and configured by the designer, and the location of programs does not change. Absolute addressing is very hard to use in general-purpose operating systems like Linux or Windows, where the user can start a variety of different programs, and their placement in the memory differs every time they're loaded and executed. Much more useful is the relative addressing where operands are specified as differences from a memory location and some known value, which can be easily modified and accessed. Often, the operands are provided relative to the Instruction Pointer, which allows the program to be loaded at any address in the address space, but the distance between the currently executed instruction and the location of the data it wants to reach is always the same. This is the default addressing mode in the Windows operating system, working on x64 machines. It is illustrated in Fig24.

Relative addressing is also implemented in many jump, branch or loop instructions.

Fundamentals of Data Encoding, Big Endian, Little Endian

The processor can work with different types of data. These include integers of different sizes, floating point numbers, texts, structures and even single bits. All this data is stored in the memory as a single byte or multiple bytes.

Integers

Integer data types can be 8, 16, 32 or 64 bits long. If the encoded number is unsigned, it is stored in binary representation, while if the value is signed, the representation is two's complement. A natural binary number range starts with zero. In such a case, it contains all bits equal to zero. While it contains all bits equal to one, the value can be calculated with the expression  , where n is the number of bits in a number.

, where n is the number of bits in a number.

In two's complement representation, the most significant bit (MSB) represents the sign of the number. Zero means a non-negative number; one represents a negative value. The table 5 shows the integer data types with their ranges.

| Number of bits | Minimum value (hexadecimal) | Maximum value (hexadecimal) | Minimum value (decimal) | Maximum value (decimal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 0x00 | 0xFF | 0 | 255 |

| 8 signed | 0x80 | 0x7F | -128 | 127 |

| 16 | 0x0000 | 0xFFFF | 0 | 65 535 |

| 16 signed | 0x8000 | 0x7FFF | -32 768 | 32 767 |

| 32 | 0x0000 0000 | 0xFFFF FFFF | 0 | 4 294 967 295 |

| 32 signed | 0x8000 0000 | 0x7FFF FFFF | -2 147 483 648 | 2 147 483 647 |

| 64 | 0x0000 0000 0000 0000 | 0xFFFF FFFF FFFF FFFF | 0 | 18 446 744 073 709 551 615 |

| 64 signed | 0x8000 0000 0000 0000 | 0x7FFF FFFF FFFF FFFF | -9 223 372 036 854 775 808 | 9 223 372 036 854 775 807 |

Floating point

Integer calculations do not always cover all mathematical requirements of the algorithm. To represent real numbers, the floating-point encoding is used. A floating point is the representation of the value A, which is composed of three fields:

- Sign bit

- Exponent (E)

- Mantissa (M)

There are two main types of real numbers, called floating-point values. Single precision is a number which is encoded in 32 bits. Double-precision floating-point number is encoded with 64 bits. They are presented in Fig25.

The Table6 shows a number of bits for exponent and mantissa for single and double precision floating point numbers. It also presents the minimal and maximal values which can be stored using these formats (they are absolute values, and can be positive or negative depending on the sign bit).

The most common representation for real numbers on computers is standardised in the document IEEE Standard 754. There are two features implemented which make the calculations easier for computers.

- The Biased exponent

- The Normalised Mantissa

A biased exponent means that the bias value is added to the real exponent value. This results in all positive exponents, which makes it easier to compare numbers. The normalised mantissa is adjusted to have only one bit of the value “1” to the left of the decimal. It requires an appropriate exponent adjustment.

Texts

Texts are represented as a series of characters. In modern operating systems, texts are encoded using two-byte Unicode, which is capable of encoding not only 26 basic letters but also language-specific characters of many different languages. In simpler computers, like in embedded systems, 8-bit ASCII codes are often used. Every byte of the text representation in the memory contains a single ASCII code of the character. It is quite common in assembler programs to use the zero value (NULL) as the end character of the string, similar to the C/C++ null-terminated string convention.

Endianness

Data encoded in memory must be compatible with the processor. Memory chips are usually organised as a sequence of bytes, which means that every byte can be individually addressed. For processors of the class higher than 8-bit, there appears to be an issue with the byte order in bigger data types. There are two possibilities:

- Little Endian - low-order byte is stored at a lower address in the memory.

- Big Endian - the high-order byte is stored at a lower address in the memory.

These two methods for a 32-bit class processor are shown in Fig26

Interrupt Controller, Interrupts

An interrupt is a request to the processor to temporarily suspend the currently executing code in order to handle the event that caused the interrupt. If the request is accepted by the processor, it saves its state and performs a function named an interrupt handler or interrupt service routine (ISR). Interrupts are usually signalled by peripheral devices in a situation when they have some data to process. Often, peripheral devices do not send an interrupt signal directly to the processor, but there is an interrupt controller in the system that collects requests from various peripheral devices. The interrupt controller prioritises the peripherals to ensure that the more important requests are handled first.

From a hardware perspective, an interrupt can be signalled with the signal state or change.

- Level triggered - stable low or high level signals the interrupt. While the interrupt handler is finished and the interrupt signal is still active, the interrupt is signalled again.

- Edge-triggered - the interrupt is signalled only while there is a change in the interrupt input. The falling or rising edge of the interrupt signal.

The interrupt signal comes asynchronously, which means that it can come during the execution of the instruction. Usually, the processor finishes this instruction and then calls the interrupt handler. To be able to handle interrupts, the processor must implement the mechanism of storing the address of the next instruction to be executed in the interrupted code. Some implementations use the stack, while others use a special register to store the return address. The latter approach requires software support if interrupts can be nested (if the interrupt can be accepted while already in another ISR).

After finishing the interrupt subroutine processor uses the returning address to return program control back to the interrupted code.

The Fig. 27 shows how interrupt works with stack use. The processor executes the program. When an interrupt comes, it saves the return address on the stack. Next jumps to the interrupt handler. With return instruction processor returns to the program, taking the address of an instruction to execute from the stack.

Recognising interrupt source

To properly handle the interrupts, the processor must recognise the source of the interrupt. Different code should be executed when the interrupt is signalled by a network controller, and different code if the source of the interrupt is a timer. The information on the interrupt source is provided to the processor by the interrupt controller or directly by the peripheral. We can distinguish three main methods of calling a proper ISR for incoming interrupts.

- Fixed – microcontrollers. Every interrupt handler has its own fixed starting address.

- Vectored – microprocessors. There is one interrupt pin; the peripheral sends the address of the handler through the data bus.

- Indexed – microprocessors. The peripheral sends an interrupt number. It is used as the index in the table of handlers' addresses.

In modern processors, interrupts can be signalled with the Message Signalled Interrupt mechanism. While the hardware needs to indicate the interrupt, it exchanges special messages through the chipset to a previously assigned memory address.

Maskable and non-maskable interrupts

Interrupts can be enabled or disabled. Disabling interrupts is often used for time-critical code to ensure the shortest possible execution time. Interrupts which can be disabled are named maskable interrupts. They can be disabled with the corresponding flag in the control register. In microcontrollers, there are separate bits for different interrupts.

If an interrupt can not be disabled is named a non-maskable interrupt. Such interrupts are implemented for critical situations:

- memory failure

- power down

- critical hardware errors

In microprocessors, there exists a separate non-maskable interrupt input – NMI.

Software and internal interrupts

In some processors, it is possible to signal the interrupt by executing special instructions. They are named software interrupts and can be used to test interrupt handlers. In some operating systems (DOS, Linux), software interrupts are used to implement the mechanism of calling system functions.

Another group of interrupts signalled by the processor itself are internal interrupts. They aren't signalled with special instructions but rather in some specific situations during normal program execution. They are called exceptions and can be divided into three groups.

- Faults – generated by abnormal behaviour in some instructions (e.g. dividing by 0).

- Traps – intentionally initiated by the programmer to transfer control to a handler routine (e.g. for debugging).

- Aborts – generated while detecting some serious errors in the program of computer behaviour (e.g. memory error).

Faults are not real errors. They are often used by the operating system to perform normal operations like handling the paging mechanism.

DMA

Direct memory access (DMA) is the mechanism for fast data transfer between peripherals and memory. In some implementations, it is also possible to transfer data between two peripherals or from memory to memory. DMA operates without the activity of the processor. No software is executed during the DMA transfer. It must be supported by a processor and peripheral hardware, and there must be a DMA controller present in the system. The controller plays the main role in transferring the data.

The DMA controller is a specialised unit which can control the data transfer process. It implements several channels, each containing the address register, which is used to address the memory location and a counter to specify how many cycles should be performed. The address and counter registers have corresponding temporal address and counter registers updated after every single transfer. The address register and counter must be programmed by the processor. It is usually done in the system startup procedure. The system with an inactive DMA controller is presented in Fig.28.

The process of data transfer is done in some steps. Let us consider the situation when a peripheral has some data to be transferred.

- peripheral signals the request to transfer data (DREQ).

- DMA controller forwards the request to the processor (HOLD).

- The processor accepts the DMA cycle (HLDA) and switches off from the buses.

- DMA controller generates the address on the address bus and sends the acknowledge signal to the peripheral (DACK).

- Peripheral sends the data on the data bus.

- DMA generates a write signal to store data in the memory.

- DMA controller updates the address register and the counter.

- If the counter reaches zero, data transfer stops.

Everything is done without any action of the processor. No program is fetched and executed. Because everything is done by hardware, the transfer can be done in one memory access cycle, so much faster than by the processor. Data transfer by the processor is significantly slower because it requires at least four instructions of program execution and two data transfers: one from the peripheral and another to the memory for one cycle. The system with an active DMA controller is presented in Fig.29.

DMA transfer can be done in some modes:

- Single - one transfer at a time

- Block (burst) - block of data at a time

- On-demand - as long as the I/O device accepts transfer

- Cycle stealing - one cycle DMA, one CPU

- Transparent - DMA works when the CPU is executing instructions

DMA controllers are implemented in personal computers, but also in advanced microcontrollers and systems on a chip, to support data transfers between internal memory and internal peripherals.

Programming in Assembler for IoT and Embedded Systems

Assembler is a low-level language that directly reflects processor instructions. It is used for programming microcontrollers and embedded devices, allowing for maximum control over the hardware of IoT systems. Programming in an assembler requires knowledge of processor architecture, which is more complex than high-level languages but offers greater efficiency. It is often used in critical applications where speed and efficiency matter. It also enables code optimization for energy consumption.

In IoT and embedded systems, an assembler enables efficient use of hardware resources, offering direct access to hardware. It is possible to use assembler code in environments like Arduino or Raspberry Pi. Assembler programs are fast and efficient, crucial in systems with limited resources. Direct control of processor registers and hardware components allows for the creation of advanced applications.

Although many libraries use assembler functions, it is often necessary to write code independently. Programming in assembler requires a deep understanding of processor architecture, which improves system design and optimization.

Evolution of the Hardware

The development of computer hardware is crucial for technology, particularly in the context of the Internet of Things (IoT) and embedded systems. The beginnings date back to the 1940s when the first electronic computers, such as ENIAC, were created.

In the 1970s, the first processors, such as the Intel 4004, appeared, revolutionizing the computer industry. Processors are advanced computing units in computers, smartphones, and other devices. Their main tasks are performing computational operations, managing memory, and controlling system components. Microprocessors are a subset of processors designed to work in more specialized devices, such as televisions or industrial equipment. They are small, efficient, and energy-saving, making them ideal for Internet of Things (IoT) applications.

Microprocessors became the foundation for the development of microcontrollers, which are the heart of embedded systems. Microcontrollers differ from processors and microprocessors in applications and functionality—small, standalone units with built-in memory, clocks, and interfaces.

Microcontrollers are complex integrated circuits designed to act as the brain of electronic devices. The central processing unit (CPU) plays a key role in their operation, controlling the microcontroller's functions and performing arithmetic and logical operations. Inside the microcontroller are registers, communication interface controllers, timers, and memory, all of which are connected by a common bus. Modern microcontrollers have built-in functions such as analog-to-digital converters (ADC) and communication interfaces (UART, SPI, I2C).

There are several types of microcontrollers, including PIC (Microchip Technology), AVR (Atmel), ESP8266/ESP32 (Espressif), and TI MSP430 (Texas Instruments).

Specific Elements of AVR Architecture